The practices of Egyptian physicians ranged from embalming, to faith healing to surgery, and autopsy. There was not the separation of Physician, Priest and Magician in Egypt. It would not be unusual for a patient to receive a bandage for a dog bite, for example, a paste of berries and honey and a incantation said over the wound as well as a magical amulet for the patient to wear. Healing was an art that was addressed on many levels.

The use of Autopsy came through the extensive embalming practices of the Egyptians, as it was not unlikely for an embalmer to examine the body for a cause of the illness which killed it. The use of surgery also evolved from a knowledge of the basic anatomy and embalming practices of the Egyptians. From such careful observations made by the early medical practitioners of Egypt, healing practices began to center upon both the religious rituals and the lives of the ancient Egyptians.

The prescription for a healthy life, (which was almost always given by a member of the priestly caste meant that an individual undertook the stringent and regular purification rituals (which included much bathing, and often times shaving one's head and body hair), and maintained their dietary restrictions against raw fish and other animals considered unclean to eat.

Also, and in addition to a purified lifestyle, it was not uncommon for the Egyptians to undergo dream analysis to find a cure or cause for illness, as well as to ask for a priest to aid them with magic, this example obviously portrays that religious magical rites and purificatory rites were intertwined in the healing process as well as in creating a proper lifestyle.

The practice of medicine was fairly advanced in Ancient Egypt, with Egyptian physicians having a wide and excellent reputation.

The Egyptians thought that most illnesses - at least those caused by no obvious accident - were the work of hostile powers: 'an adversary male or female, a spirit or a dead person' and it was for this reason that magicians, as well as physicians were concerned with curing the ills of the populace.

Insect, especially scorpion bites or snake bites, both very frequent in Egypt, were treated by magicians, as there appears to have been no specific balm or ointment used, and as we have records of many spells, written on papyri and magical charms devoted to these two occurrences.

Much documentation exists that in addition to magicians, useful in the villages and countryside, there existed a much less primitive form of medicine.

Texts of the time frequently mention doctors, oculists, dentists and other specialists, including veterinarians.

Doctors and other medical personnel kept detailed notes (on papyrus) describing the condition encountered, and the treatment applied in all areas of medicine, including gynecology, bone surgery and eye complaints, the latter of which was very frequent in the dry, dusty climate of the country.

Texts on anatomy and physiology exist, showing a degree of knowledge of the workings of the human body, its structure, the job of the heart and blood vessels, including, the 'treatise of the heart' contained in the Ebers Papyrus. However, despite the process of mummification, familization with the human body was not as highly developed as would be expected and many fantastic and fanciful definitions and descriptions may be found in the Ancient texts.

Ancient Egyptians knew little about the existence, for instance, of the kidneys and made the heart the meeting point of a number of vessels which carried all the fluids of the body (from blood, which is correct), to tears, urine and sperm (which is less so).

Many prescriptions exist today, showing treatment of many disorders and the use of a variety of substances, plant, animal, mineral, as well as the droppings and urine of a number of animals (pelicans, hippopotami, etc.), which were present in large numbers along the Nile. Honey and milk were routinely prescribed by physicians for the treatment of the respiratory system, and throat irritations. The physicians of the day knew how to use suppositories, herbal dressings and enemas and widely used castor oil.

Medications used for the urinary tract show that they, as do their modern Egyptians, suffered from bilharzia (a parasite). Head injuries were routinely, and it would appear, successfully treated by trepenning, the opening of the skull to relieve pressure, migraines, which were attributed to dental trouble and accidents involving the eye. Teeth were filled using a type of mineral cement, and gum disease were also treated.

Gold was used to bind loose teeth, and the jaw-bone was at times perforated to drain abscesses. As eye disease was a big problem, due to dust, flies and poor hygiene, many prescriptions have been found, to cure trachoma (endemic to this day in Egypt), cataract and a form of night blindness. This last aliment was correctly treated using animal liver, as, to this day, extracts of liver are also used.

Bone surgery was particularly well developed, researching the proportions of scientific research. The Papyrus of Edwin Smith deals extensively with bruises of the vertebra, dislocation of the jaws, various fractures (of the clavicle, humerus, ribs, nose and cranium. Egyptians physicians also recognized diseases which could not be treated: "An affliction for which nothing can be done".

Although many of the treatments used had little or no value (from our modern vantage-point), Egyptian medicine had a well deserved reputation throughout the Ancient World, with, for instance, Hippocrates and Galan acknowledging that part of their information came from Egyptian works which they had studied at the temple of Imhotep at Memphis.

Sanctuaries of the Gods often had sanatoria attached to them, allowing physicians, and physician-priests to treat the pilgrims, and perform "miraculous healings", and the publicizing of the cures performed by Amenhotep, son of Hapu, Imhotep and Serapis, further spreading the fame of Egyptian medical science.

- The Ancient Egyptian Virtual Temple

1) knives; (2) drill; (3) saw; (4) forceps or pincers; (5) censer; (6) hooks; (7) bags tied with string; (8, 10) beaked vessel; (11) vase with burning incense; (12) Horus eyes; (13) scales; (14) pot with flowers of Upper and Lower Egypt; (15) pot on pedestal; (16) graduated cubit or papyrus scroll without side knot (or a case holding reed scalpels); (17) shears; (18) spoons.

- Ancient Egyptian Virtual Temple

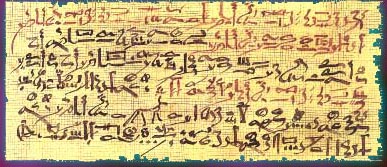

The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus is, without a doubt, one if the most important documents pertaining to medicine in the ancient Nile Valley.

It was written around1700 BC but most of the information is based on texts written around 2640 BC - Imhoteps time.

The papyrus appears to talk mainly about wounds, and how to treat them, and suprisingly little about diseases.

Placed on sale by Mustafa Agha in 1862, the papyrus was purchased by Edwin Smith. An American residing in Cairo, Smith has been described as an adventurer, a money lender, and a dealer of antiquities. Smith has also been reputed as advising upon, and even practicing, the forgery of antiquities. Whatever his personal composition, it is to his credit that he immediately recognized the text for what it was and later carried out a tentative translation. Upon his death in 1906, his daughter donated the papyrus in its entirety to the New York Historical Society.

In 1930, James Henry Breasted, director of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, published the papyri with facsimile, transcription, English translation, commentary, and introduction. The volume was accompanied by medical notes prepared by Dr. Arno B. Luckhardt. To date, the Breasted translation is the only one if its kind.

The Edwin Smith papyrus is second in length only to the Ebers papyrus, comprising seventeen pages (377 lines) on the recto and five pages (92 lines) on the verso. Both the recto and the verso are written with the same hand in a style of Middle Egyptian dating.

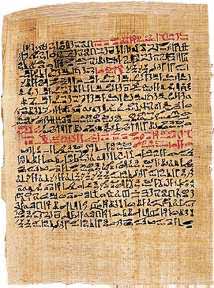

Like the Edwin Smith Papyrus, the Ebers Papyrus was purchased in Luxor by Edwin Smith in 1862. It is unclear from whom the papyrus was purchased, but it was said to have been found between the legs of a mummy in the Assassif district of the Theben necropolis.

The papyrus remained in the collection of Edwin Smith until at least 1869 when there appeared, in the catalog of an antiquities dealer, and advertisement for "a large medical papyrus in the possession of Edwin Smith, an American farmer of Luxor."(Breasted 1930) The Papyrus was purchased in 1872 by the Egyptologist George Ebers, for who it is named. In 1875, Ebers published a facsimile with an English-Latin vocabulary and introduction.

The Ebers Papyrus comprises 110 pages, and is by far the most lengthy of the medical papyri. It is dated by a passage on the verso to the 9th year of the reign of Amenhotep I (c. 1534 B.C.E.), a date which is close to the extant copy of the Edwin Smith Papyrus. However, one portion of the papyrus suggests a much earlier origin. Paragraph 856a states that : "the book of driving wekhedu from all the limbs of a man was found in writings under the two feet of Anubis in Letopolis and was brought to the majesty of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt Den."(Nunn 1996: 31) The reference to the Lower Egyptian Den is a historic anachronism which suggesting an origin closer to the First Dynasty (c. 3000 B.C.E.)

Unlike the Edwin Smith Papyrus, the Ebers Papyrus consists of a collection of a myriad of different medical texts in a rather haphazard order, a fact which explains the presence of the above mentioned excerpt. The structure of the papyrus is organized by paragraph, each of which are arranged into blocks addressing specific medical ailments.

Paragraphs 1-3 contain magical spells designed to protect from supernatural intervention on diagnosis and treatment. They are immediately followed by a large section on diseases of the stomach (khet), with a concentration on intestinal parasites in paragraphs 50-85.(Bryan 1930:50) Skin diseases, with the remedies prescribed placed in the three categories of irritative, exfoliative, and ulcerative, are featured in paragraphs 90-95 and 104-118.

Diseases of the anus, included in a section of the digestive section, are covered in paragraphs 132-164.(Ibid. 50) Up to paragraph 187, the papyrus follows a relatively standardized format of listing prescriptions which are to relieve medical ailments. However, the diseases themselves are often more difficult to translate. Sometimes they take the form of recognizable symptoms such as an obstruction, but often may be a specific disease term such as wekhedu or aaa, the meaning of both of which remain quite obscure.

Paragraphs 188-207 comprise "the book of the stomach," and show a marked change in style to something which is closer to the Edwin Smith Papyrus.(Ibid.: 32) Only paragraph 188 has a title, though all of the paragraphs include the phrase: "if you examine a man with aŠ," a characteristic which denotes its similarity to the Edwin Smith Papyrus. From this point, a declaration of the diagnosis, but no prognosis. After paragraph 207, the text reverts to its original style, with a short treatise on the heart (Paragraphs 208-241).

Paragraphs 242-247 contains remedies which are reputed to have been made and used personally by various gods. Only in paragraph 247, contained within the above mentioned section and relating to Isis' creation of a remedy for an illness in Ra's head, is a specific diagnosis mentioned. (Bryan 1930:45)

The following section continues with diseases of the head, but without reference to use of remedies by the gods. Paragraph 250 continues a famous passage concerning the treatment of migraines. The sequence is interrupted in paragraph 251 with the focus placed on a drug rather than an illness. Most likely an extract from pharmacopoeia, the paragraph begins: "Knowledge of what is made from degem (most likely a ricinous plant yielding a form of castor oil), as something found in ancient writings and as something useful to man."(Nunn 1996: 33)

Paragraphs 261-283 are concerned with the regular flow of urine and are followed by remedies "to cause the heart to receive bread."(Bryan 1930:80). Paragraphs 305-335 contain remedies for various forms of coughs as well as the genew disease.

The remainder of the text goes on to discuss medical conditions concerning hair (paragraphs 437-476), traumatic injuries such as burns and flesh wounds (paragraphs 482-529), and diseases of the extremities such as toes, fingers, and legs. Paragraphs 627-696 are concerned with the relaxation or strengthening of the metu. The exact meaning of metu is confusing and could be alternatively translated as either mean hollow vessels or muscles tissue.(Ibid.:52)

The papyrus continues by featuring diseases of the tongue (paragraphs 697-704), dermatological conditions (paragraphs 708-721), dental conditions (paragraphs 739-750), diseases of the ear, nose, and throat (paragraphs 761-781), and gynecological conditions (paragraphs 783-839)

The Kahun Papyrus was discovered by Flinders Petrie in April of 1889 at the Fayum site of Lahun. The town itself flourished during the Middle Kingdom, principally under the reign of Amenenhat II and his immediate successor.

The papyrus is dated to this period by a note on the recto which states the date as being the 29th year of the reign of Amenenhat III (c. 1825 B.C.E.). The text was published in facsimile, with hieroglyphic transcription and translation into English, by Griffith in 1898, and is now housed in the University College London.

The gynecological text can be divided into thirty-four paragraphs, of which the first seventeen have a common format.(Nunn 1996: 34) The first seventeen start with a title and are followed by a brief description of the symptoms, usually, though not always, having to do with the reproductive organs.

The second section begins on the third page, and comprises eight paragraphs which, because of both the state of the extant copy and the language, are almost unintelligible. Despite this, there are several paragraphs that have a sufficiently clear level of language as well as being intact which can be understood.

Paragraph 19 is concerned with the recognition of who will give birth; paragraph 20 is concerned with the fumigation procedure which causes conception to occur; and paragraphs 20-22 are concerned with contraception. Among those materials prescribed for contraception are crocodile dung, 45ml of honey, and sour milk.

The third section (paragraphs 26-32) is concerned with the testing for pregnancy. Other methods include the placing of an onion bulb deep in the patients flesh, with the positive outcome being determined by the odor appearing to the patients nose.

The fourth and final section contains two paragraphs which do not fall into any of the previous categories. The first prescribes treatment for toothaches during pregnancy. The second describes what appears to be a fistula between bladder and vagina with incontinence of urine "in an irksome place."

Tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis)

Ruffer (1910) reported the presence of tuberculosis of the spine in Nesparehan, a priest of Amun of the 21st Dynasty. This shows the typical features of Pott's disease with collapse of thoracic vertebra, producing the angular kyphosis (hump-back). A well known complication of Pott's disease is the tuberculous suppuration moving downward under the psoas major muscle, towards the right iliac fossa, forming a very large psoas abscess.(Nunn 1996:64)

Ruffer's report has remained the best authenticated case of spinal tuberculosis from ancient Egypt. All known possible cases, ranging from the Predynastic to 21st Dynasty were reviewed by Morse, Brockwell, and Ucko (1964) as well as by Buikstra, Baker, and Cook.(1993) These included Predynastic specimens collected at Naqada by Petrie and Quibell in 1895 as well as nine Nubian Specimens from the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Both reviewers were in agreement that there was very little doubt that tuberculosis was the cause of pathology in most, but not all, cases. In some cases, it was not possible to exclude compression fractures, osteomyelitis, or bone cysts as causes of death.

The numerous artistic representation of hump-backed individuals are provocative but not conclusive. The three earliest examples are undoubtedly of Predynastic origin. The first is a ceramic figurine reported to have been found by Bedu in the Aswan district. It represents an emaciated human with angular kyphosis of the thoracic spine crouching in a clay vessel.(Schrumph-Pierron 1933) The second possible Predynastic representation with spinal deformity indicative of tuberculosis is a small standing ivory likeness of a human with arms down at the sides of the body bent at the elbows.

The head is modeled with facial features carefully indicated. The figure is shown with a protrusion of the back and on the chest.(Morse 1967: 261) The last Predynastic example is a wooden statue contained within the Brussels Museum. Described as a bearded male with intricate facial features, the figure has a large rounded hunch-back and an angular projection of the sternum.(Jonckheere 1948: 25)

As well, there are several historic Egyptian representations which indicate the possibility of tuberculosis deformity. One of the most suggestive, located in and Old Kingdom 4th Dynasty tomb, is of a bas relief serving girl who exhibits localized angular kyphosis. A second provocative example has its origin in the Middle Kingdom. A tomb painting at Beni Hasan, the representation shows a gardener with a localized angular deformity of the cervical-thoracic spine.(Morse 1967: 263)

Poliomyelitis

A viral infection of the anterior horn cells of the spinal chord, the presence of poliomyelitis can only be detected in those who survive its acute stage. Mitchell (Sandison 1980:32) noted the shortening of the left leg, which he interpreted as poliomyelitis, in the an early Egyptian mummy from Deshasheh. The club foot of the Pharaoh Siptah as well as deformities in the 12th Dynasty mummy of Khnumu-Nekht are probably the most attributable cases of poliomyelitis.

An 18th or 19th Dynasty funerary staele shows the doorkeeper Roma with a grossly wasted and shortened leg accompanied by an equinus deformity of the foot. The exact nature of this deformity, however, is debated in the medical community.

Some favor the view that this is a case of poliomyelitis contracted in childhood before the completion of skeletal growth. The equinus deformity, then, would be a compensation allowing Roma to walk on the shortened leg. Alternatively, the deformity could be the result of a specific variety of club foot with a secondary wasting and shortening of the leg.(Nunn 1996: 77)

Dwarfism:

Dasen (1993) lists 207 known representations of dwarfism. Of the types described, the majority are achondroplastic, a form resulting in a head and trunk of normal size with shortened limbs. The statue of Seneb is perhaps the most classic example. A tomb statue of the dwarf Seneb and his family, all of normal size, goes a long way to indicate that dwarfs were accepted members in Egyptian society. Other examples called attention to by Ruffer (1911) include the 5th Dynasty statuette of Chnoum-hotep from Saqqara, a Predynastic drawing of the "dwarf Zer" from Abydos, and a 5th Dynasty drawing of a dwarf from the tomb of Deshasheh.

Skeletal evidence, while not supporting the social status of dwarfs in Egyptian society, does corroborate the presence of the deformity. Jones described a fragmentary Predynastic skeleton from the cemetery at Badari with a normal shaped cranium both in size in shape. In contrast to this, however, the radii and ulna are short and robust, a characteristic of achondroplasia. A second case outlined by Jones consisted of a Predynastic femur and tibia, both with typical short shafts and relatively large articular ends.

- Breasted, J.H. The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus

January 2002 - Reuters - NY

Can't beat that headache? Why not try an incantation to falcon-headed Horus, or a soothing poultice of "Ass's grease"? According to researchers, 3,500-year-old papyri show ancient Egyptians turning to both their gods and medicine to banish headache pain.

"The border between magic and medicine is a modern invention; such distinctions did not exist for ancient healers," explain Dr. Axel Karenberg, a medical historian, and Dr. C. Leitz, an Egyptologist, both of the University of Cologne, Germany.

In a recent issue of the journal Cephalalgia, the researchers report on their study of papyrus scrolls dating from the early New Kingdom period of Egyptian history, about 1550 BC.

Ancient Egyptian healers had only the barest understanding of anatomy or medicine. Indeed, while the head was considered the "leader" of the body, the brain itself was considered relatively unimportant--as evidenced by the fact that it was usually discarded during the mummification process.

Headache, that timeless bane of humanity, was usually ascribed to the activity of "demons," the German researchers write, although over time Egyptian physicians began to speculate that problems originating within the body, such as the incomplete digestion of food, might also be to blame.

Once beset with a headache, those living under the pharaohs turned to their gods for help. One incantation sought to evoke the gods' empathy, imagining that even immortals suffered headache pain.

"'My head! My head!' said Horus," reads one papyrus. "'The side of my head!' said Thoth. 'Ache of my forehead,' said Horus. 'Upper part of my forehead!' said Thoth."

In this way, Karenberg and Leitz write, "the patient is identified with (the gods) Horus and Thoth," the latter being the god of magicians and wise men.

The incantation continues with the sun god Ra ordering the patient to recover "up to your temples," while the patient threatens his "headache demons" with terrible punishments ("the trunk of your body will be cut off").

Still, the gods may have ignored the pleas of many patients, who also turned to medicine for relief. According to one ancient text, these included a poultice made of "skull of catfish," with the patient's head being "rubbed therewith for four days."

Other prescriptions included stag's horn, lotus, frankincense and a concoction made from donkey called "Ass's grease."

Even these remedies could be divinely inspired, however. On one 4,000-year-old scroll, a boastful druggist claims that his headache cure is prepared by the goddess Isis herself.

0 comments:

Post a Comment