The Red Pyramid at Dashur also known as the Shining Pyramid, is one of three (or maybe even four) pyramids built by the great Pharaoh Snefru the first pharaoh of the 4th Dynasty, father of Khufu (supposed builder of the Great Pyramid), who reigned from 2575-2551 BC - in Egypt's Old Kingdom. It is the first true pyramid still remaining.

The Red Pyramid gets its name from the reddish or pinkish limestone, used in its casing stones. The total area of the structure is only slightly less than the Great Pyramid, but as the angle of inclination of its sides is much shallower (43 degrees 22''), it only reaches a height of 341 feet (104m ).

The interior of the pyramid is quite interesting. The entrance is in its Northern face, as is common with nearly all pyramids in Egypt.

A descending passage takes you along about 80 metres before levelling out and opening out into two seperate underground chambers, connected by another short tunnel. Both of these chambers have magnificent corbelled roofs, a photo of which can be seen below.

A further passageway, at a considerable height above the level of the floor, leads to a third chamber, with a corbelled roof that rises 50 feet into the body of the pyramid.

No trace of a burial has ever been found in this pyramid, the inside is completely uninscribed and therefore it is, to all intents and purposes, anonymous.

Two and a half miles (4 km) to the north of the bent Pyramid lies Snefru's third pyramid.

Called the 'Red Pyramid' after the rusty tinge of the local limestone of its core, it would become Snefru's final resting place.

Quick to learn from their mistakes, this time the king's architects laid a foundation platform of several courses of fine white limestone to prevent the problem of subsidence from recurring. The lesson of the Bent Pyramid also encouraged them to construct the pyramid with stones laid in level, rather than inclined, courses at the similarly modest angle of 43 degrees to a not insubstantial height of 104 m (341 ft), making it the fourth highest pyramid ever built.

With its construction, pyramids left the arena of experimentation and finally achieved the distinctive and proper geometric form they would retain until their building ceased. The perfection achieved on the exterior of the Red Pyramid is matched by the elegance of its internal chambers. A long descending corridor entered from the north side of the pyramid led to three rooms, over 12 m (40 ft) high and built of enormous limestone blocks.

Two connecting chambers were at ground level within the base of the pyramid, but the third was shaped within the masonry of the pyramid itself. It could only be entered via a carefully concealed passage in the wall of the second chamber, some 7.6 m (25 ft) above its floor. According to Rainer Stadelmann, 'With this marvelous sequence of large and high rooms, King Snefru finally had achieved a burial place he could be happy and content with. It was his eternal residence, built with absolute perfection.' he has studied the Red Pyramid for over 20 years.

The most stunning aspect of these rooms is the corbelled ceilings, the blocks of which were placed in eleven to fourteen layers, each one protruding out over the room about 15 cm (6 in) on all four sides until a pyramid-shaped roof was obtained. In this ingenious way, the weight of the pyramid could be supported. More than two million tonnes of stone rested on these ceilings, yet there are no cracks, no subsidence. Not only had the architects tackled the vexing problems of construction, but by creating a pyramid within a pyramid, they reinforced the king's chances of resurrection.

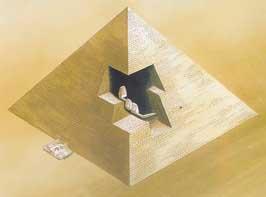

This isometric drawing of the Red Pyramid shows the internal system of three chambers entered by a sloping corridor from the north side. The temple complex on the east of his pyramids was another of Snefru's innovations.

Stadelmann discoveries have added considerably to our understanding of Snefru's reign and vision. But one discovery in particular has helped to answer the age-old question of how long it took to build a pyramid. Stadelmann explains: 'When we started excavating here we found part of the outer casing still preserved, but a lot of blocks had fallen or were displaced. On the reverse of these loose stones we found inscriptions in red paint naming the working gangs who constructed the pyramid, for examples, the "Green Gang" or the "Western Gang".

We also found the name of Snefru in a cartouche. I would say about every twentieth stone was inscribed, but the most exciting thing was that dates were also written on the backs of these blocks.

From these dates, Stadelmann has been able to determine the sequence of work. An inscription on one of the foundation blocks dates to the beginning of construction to the fifteenth census count undertaken during Snefru's reign, perhaps equivalent to his twenty-second or twenty-ninth year on the throne.

Two years later, six layers of stone had been laid. Within four years 15 m (49 ft), or about 30 per cent, of the pyramid were already completed. When studied together, the inscriptions show that it took about seventeen years to construct the entire pyramid. To celebrate its completion, the proud builders added a solid limestone pyramid-shaped capstone, called today a 'pyramidion'.

To the Egyptians, it was the benbenet, the very tip of that mound of creation where the creator god stood when he created the world. Placed on top of these soaring mounds of masonry, it joined the earth with the sky. Few pyramidions from the Pyramid Age survive, possibly because many were gilded with precious metals. The earliest one now known was discovered in fragments around the base of the Red Pyramid. After painstaking restoration, Stadelmann found that each side had a slightly different angle; even with all of their experience in construction, the Egyptians had trouble reaching the top without some readjustments. Such mistakes remind us of the human elements in these austere piles; nevertheless, the error is extraordinarily small - only 2 degrees over 102 m (335 ft), almost 160 courses of stone! Such a minimal readjustment is, in fact, a true testimony to the abilities of Snefru's architects.

To complete such a pyramid in seventeen years is an even more impressive feat when one considers that at the same time Snefru was hedging his bets by filling in the steps of the pyramid at Meidum, transforming it too into a geometric pyramid, a shape for which he and his architects deserve full credit.

But with this change in shape also came a transformation of the concept of the afterlife and a modification of the complex necessary to ensure it. The shape and orientation of the pyramid complexes of Snefru's anceseors suggest they looked to the stars, linking their journey to the afterlife with the never-setting circumpolar stars, 'the imperishable ones', as they called them.

But while they ascended their staircase to the stellar sphere, Snefru trod a ramp of gleaming white limestone like the sun's rays to heaven. To reinforce this connection Snefru laid out his temples along a new east-west alignment in accordance with the course of the sun. This new emphasis on the sun led to the adoption of an entirely new name, a new manifestation, of the king on his ascension to the throne as the 'Son of Ra', the son of the sun god, a father he would join in the afterlife. Snefru pioneered his new axial design for his resurrection machine at all three of his pyramids, but his son and successors at Giza perfected it.

0 comments:

Post a Comment