The temples were was the House of Worships to the many the Gods and Goddesses the ancent Egyptians worshipped. All was to be kept clean and in order according to the laws of Maat. If not - the god or goddess would leave and great unrest would result for Egypt.

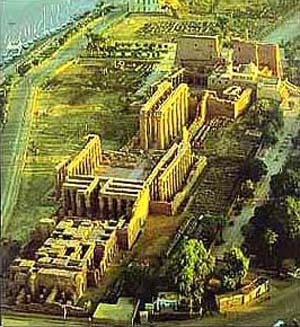

Temples were found everywhere. Each city had a temple built for the god of that city. The purpose of the temple was to be a cosmic center by which men had communication with the gods. As the priests became more powerful, tombs became a part of great temples. Shown below is a typical temple flood plan with the purposes of each section given.

There are two parts of the temple; the outer temple where the beginning initiates are allowed to come, and the inner temple where one can enter only after proven worthy and ready to acquire the higher knowledge and insights.

The highest priest for any and all gods was of course Pharaoh, who in his turn appointed high priests and other priests to perform his duties to the gods. And it was only Pharaoh or the priest on duty who was ever allowed into the innermost chamber of the temple, where the naos was kept (the shrine built of wood), where the statue of the god was situated. This they did only at the morning ceremony, the midday and evening ceremony. At all other times noone entered that part of the temple.

The rest of the priesthood were the only ones who were allowed beyond the outer court. The worshippers (the Shemsu) were never allowed further than the outer court, where they could leave their offerings to priests who brought them into the temple. So the temple was indeed considered the home of the god, it did not function like the temples of other cultures where people come and go more or less as they please. These temple precincts were the domains of the god, who was believed to be resident in actual fact.

The most important task of the priesthood was to see to it that the god was well cared for and got everything that he could need. They were indeed "servants of the god". They had the duty to ensure that the god wanted to remain in his home and in Egypt so that all would be well. If he were to be discontent he would no longer protect the land but leave it.

But the relationship between the average Egyptian and his god was nevertheless an intense one. Those who lived near an important cult center or even a smaller temple could always go to the outer court and leave their offerings and there was also a backdoor behind the main building where they could hand in their ostraca on which they had scribbled prayers and questions, or they could whisper their troubles to an attending priest. The priests took care of it and usually provided the questioner with an answer of sorts.

Then there were the festival days when the god was carried on his bargue in procession through the city. At those occasions the processinal route was lined with worshippers and residents who came to get a glimpse of the statue, even though it was usually hidden with hangings and shaded with great ostrich feathers. These festive occasions were much cherished and longed for, and it was probably allowed then for the commoner to enter the temples and, after having made a suitable offering he could perhaps wander across the holy courtyards and maybe visit the place where the sacred animals were kept.

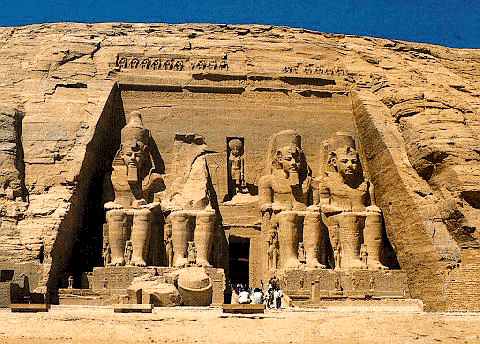

The Great Temple of Abu Simbel

This is the Great Temple of Abu Simbel. The temple was cut into rock in the 13th century B.C. by the famous pharaoh Ramses II in honour of himself and the triad Amon-Ra, Ptah and Ra-Harakhte. Together with a smaller temple dedicated to Ramses' wife Nefertari and the goddess Hathor, it lay strategically in a bend of the river Nile overlooking the plains to the south as an impressive monument of Egypt's might. As such it must have served to impress people coming from the south, possibly to scare anyone thinking of invading the land of Egypt. The temple's strategical position proved unfortunate for its placement right at the bank of the Nile, because the building of a new dam in the Nile in the 1960s caused the water to rise to its feet, and threatened to eventually drown the great monument. During a great international rescue campaign headed by UNESCO between 1963 and 1967 the temple was moved to a higher and safe location.

The front of the temple is dominated by four gigantic statues of the great pharaoh himself. The colossi of the king, wearing the characteristic nemes headcloth and double crown (of upper and lower Egypt), are each 20 metres high, while the facade is more than 35 metres wide and 30 metres high. The king is accompanied by some of his wives, sons and daughters who appear in much smaller size beside his legs. Right above the entrance stands a figure of the god Re-Harakhte in a small niche. The top of the facade is crowned by a row of baboons.

The central entrance leads into a large hall with massive pillars fronted by Osiris figures of the king. The temple's orientation is arranged in such a way that twice every year on 22 February and 22 October the earliest sun-rays shine on the back wall of the innermost chamber, thus illuminating the statues of the four gods seated there.

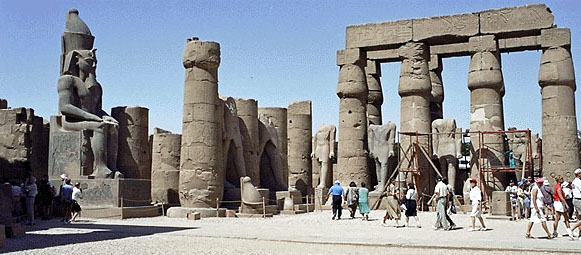

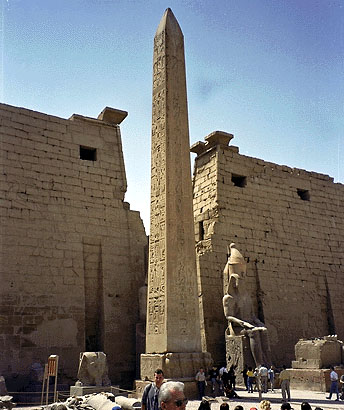

The modern town of Luxor is the site of the famous city of Thebes, (Waset in ancient Egyptian) the city of a hundred gates. It was the capital of Egypt from the 12th dynasty (1991 BC) and reached its zenith during the New Kingdom. It was from here that Thutmose III planned his campaigns, Akenaten first contemplated the nature of god and Rameses II set out his ambitious building program. Only Memphis could compare in size and wealth, but Memphis was pillaged of its masonry to build new cities and little remains. Although the mud brick palaces of Thebes have disappeared the stone built temples have survived.

This temple has been in almost continuos use as a place of worship right up to the present day. It was completed by Tutankhamun and Horemheb and added to by Ramses II. Towards the rear is a granite shrine dedicated to Alexander the Great.

During the Christian era the temple's hypostyle hall was converted into a Christian church, and the remains of another Coptic church can be seen to the west.

Then for thousands of years, the temple was buried beneath the streets and houses of the town of Luxor. Eventually the mosque of Sufi Shaykh Yusuf Abu al-Hajjaj was built over it. This mosque was preserved when the temple was uncovered and forms an integral part of the site today.

Many festivals were celebrated in Thebes. The Temple of Luxor was the center of the most important one, the festival of Opet. Built largely by Amenhotep III and Ramesses II, it appears that the temple's purpose was for a suitable setting for the rituals of the festival.

The festival itself was to reconcile the human aspect of the ruler with the divine office. During the 18th Dynasty the festival lasted eleven days, but had grown to twenty-seven days by the reign of Ramesses III in the 20th Dynasty. At that time the festival included the distribution of over 11,000 loaves of bread, 85 cakes and 385 jars of beer.

The procession of images of the current royal family began at Karnak and ended at the temple of Luxor. By the late 18th Dynasty the journey was being made by barge, on the Nile River. Each god or goddess was carried in a separate barge that was towed by smaller boats.

Large crowds consisting of soldiers, dancers, musicians and high ranking officials accompanied the barge by walking along the banks of the river. During the festival the people were allowed to ask favors of the statues of the kings or to the images of the gods that were on the barges. Once at the temple, the king and his priests entered the back chambers.

There, the king and his ka (the divine essence of each king, created at his birth) were merged, the king being transformed into a divine being. The crowd outside, anxiously awaiting the transformed king, would cheer wildly at his re-emergence. This solidified the ritual and made the king a god.

The festival was the backbone of the pharaoh's government. In this way could a usurper or one not of the same bloodline become ruler over Egypt.

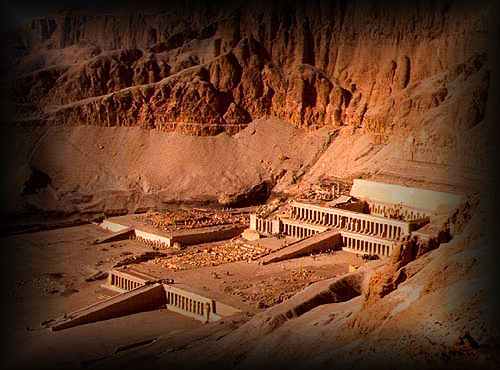

The mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut is one of the most dramatically situated in the world. The queen's architect, Senenmut, designed it and set it at the head of a valley overshadowed by the Peak of the Thebes, the "Lover of Silence," where lived the goddess who presided over the necropolis.

A tree lined avenue of sphinxes led up to the temple, and ramps led from terrace to terrace. The porticoes on the lowest terrace are out of proportion and coloring with the rest of the building. They were restored in 1906 to protect the celebrated reliefs depicting the transport of obelisks by barge to Karnak and the miraculous birth of Queen Hatshepsut.

Reliefs on the south side of the middle terrace show the queen's expedition by way of the Red Sea to Punt, the land of incense. Along the front of the upper terrace, a line of large, gently smiling Osirid statues of the queen looked out over the valley. In the shade of the colonnade behind, brightly painted reliefs decorated the walls.

Throughout the temple, statues and sphinxes of the queen proliferated. Many of them have been reconstructed, with patience and ingenuity, from the thousands of smashed fragments found by the excavators; some are now in the Cairo Museum, and others the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

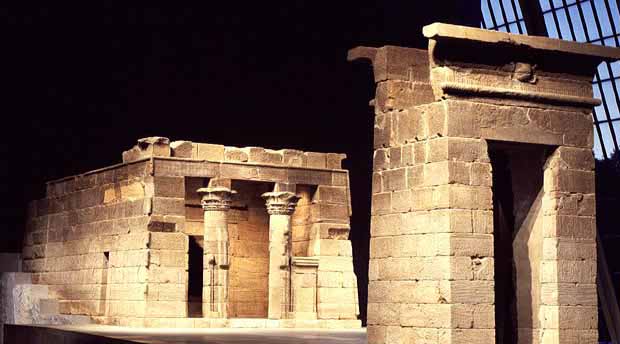

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

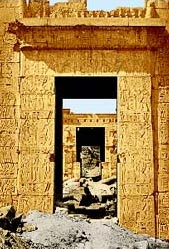

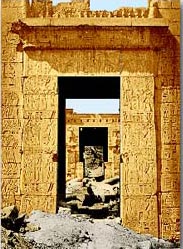

Located at Fayoum, Narmuthis is so vast it is not completely excavated. Built by Amenemhet III the temple is dedicated to the gods Sobek, Ernutet and Horus. Guarded by sphinxes and lions, the temple's interior walls are covered with hieroglyphics and reliefs of Amenemhet III and Amenemhet IV. From an archeology viewpoint, this is considered to be the most interesting site in Faiyum.

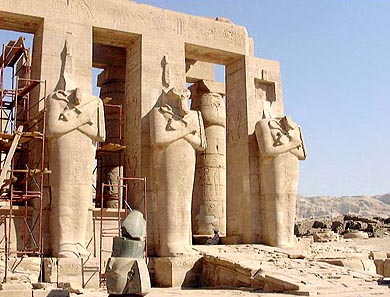

Ramesses II built the fabulous mortuary temple on the site of Seti I's ruined temple.

This great temple reportedly rivaled the wonders of the temple at Abu Simbel.

However, Ramesses built the temple too close to the Nile and the flood waters took their toll. Only a single colonnade remains of the First Courtyard. In frontof the ruins is the base of the colossus of Ramesses that once stood 17m high. The statue would have weighed more than 1,000 tons. The statue fell into the Second Court and the head and torso remain there, but the other broken pieces are in museums all over the world. The ceiling in the Astronomical Room is still intact with the illustration of the oldest known 12 month calendar.

The entire Temple of Ramesses III, palace and town is enclosed within a defensive wall. Entry is through the Highgate, or Migdol, which, in appearance resembles an Asiatic fort. Just inside the Highgate, to the south, are the chapels of Amenirdis I, Shepenwepet II and Nitoket, wives of the god Amun. To the north side is the chapel of Amun. These chapels were a later addition dating to the 18th Dynasties, by Hatsepsut and Tutmose II. Later renovations were done by the Ptolemaic kings of the XXV Dynasty.

To the west is the temple proper, which was styled after the Ramesseum. On the north wall of the temple are reliefs depicting the victory of Ramesses with the Sardinians, Cretans, Philistines and the Danu. This was perhaps the greatest victory in ancient Egypt. Pharaoh watched as the invaders crossed the plains, destroying everything in their path. The multitude came with oxen-drawn wagons, laden down with all of their possessions, their families and their newly discovered iron weapons. No tribe or settlement was able to survive their passing. The horde came over the land and the sea heading straight for Egypt.

Rameses gathered together his army and defeated the land invaders. He then proceeded to the shore to meet the ships. Ramesses archers released their arrows against the landing ships. (The Egyptians's had an advantage over the enemy; the Egyptian's ships had both sails and oars, while the invader's had only the sail.) The Egyptian army then rowed out to sea and overturned the invaders' ship, drowning all that survived the archers' attack.

These are the only know reliefs of a sea battle in Egypt. The Egyptians were excellent accountants and counted everything that was taken from the enemy and all that were slain. The reliefs show the bookkeepers counting the spoils. Entering through the massive Pylon (27m high and 65m long) is the First Court where athletic sporting events, such as wrestling, were held. Reliefs on the south wall are of Ramesses' victory over the Libyans and the Window of Appearances is on the west wall, flanked by eight columns. Behind this lies the audience hall with the kings' shower room nearby. The stone tank is still intact. On the east side are seven Osiride pillars.

The Second Court, accessed via ramp up and through the Pylon, is made up of eight Osiride pillars and six columns. Of the scenes in the Second Court are the Feast of Sokar and the lower part of the back wall being dedicated to Ramesses children. Of interest in the entrance at the right end of the hall is a relief of Ramesses kneeling on the symbol of Upper and Lower Egypt and a defaced scene of Ramesses before Seth, with the Pharaoh changed into Horus. The Hypostyle Hall through the west entrance was badly damaged in 27 B.C. by an earthquake. Originally, The Hall would have opened into many rooms but none remain due to the earthquake.

Close to the temple is the remains of a Nilometer. These 'flood warnings' were positioned strategically along the river to determine the position of the river every year. Not only did these register the height of the river, but also determined the amount of silt that was being deposited. With this information, the governors could, in advance, determine which crop would thrive and thus base the tax levy.

PROVERBS FROM TEMPLES

0 comments:

Post a Comment