Dunhuang has 492 caves, with 45,000 square meters of frescos, 2, 415 painted statues and five wooden-structured caves. The Mogao Grottoes contain priceless paintings, sculptures, some 50,000 Buddhist scriptures, historical documents, textiles, and other relics that first stunned the world in the early 1900s.

The Mogao Caves, or Mogao Grottoes (also known as the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas and Dunhuang Caves) form a system of 492 temples 25 km (15.5 miles) southeast of the center of Dunhuang, an oasis strategically located at a religious and cultural crossroads on the Silk Road, in Gansu province, China. The caves contain some of the finest examples of Buddhist art spanning a period of 1,000 years. Construction of the Buddhist cave shrines began in 366 AD as places to store scriptures and art. The Mogao Caves are the best known of the Chinese Buddhist grottoes and, along with Longmen Grottoes and Yungang Grottoes, are one of the three famous ancient sculptural sites of China

According to local legend, in 366 AD a Buddhist monk, Le Zun , had a vision of a thousand Buddhas and inspired the excavation of the caves he envisioned. The number of temples eventually grew to more than a thousand. As Buddhist monks valued austerity in life, they sought retreat in remote caves to further their quest for enlightenment. From the 4th until the 14th century, Buddhist monks at Dunhuang collected scriptures from the west while many pilgrims passing through the area painted murals inside the caves. The cave paintings and architecture served as aids to meditation, as visual representations of the quest for enlightenment, as mnemonic devices, and as teaching tools to inform illiterate Chinese about Buddhist beliefs and stories.

The murals cover 450,000 square feet. The caves were walled off sometime after the 11th century after they had become a repository for venerable, damaged and used manuscripts and hallowed paraphernalia.

In the early 1900s, a Chinese Taoist named Wang Yuanlu appointed himself guardian of some of these temples. Wang discovered a walled up area behind one side of a corridor leading to a main cave. Behind the wall was a small cave stuffed with an enormous hoard of manuscripts dating from 406 to 1002 AD. These included old hemp paper scrolls in Chinese and many other languages, paintings on hemp, silk or paper, numerous damaged figurines of Buddhas, and other Buddhist paraphernalia.

The subject matter in the scrolls covers diverse material. Along with the expected Buddhist canonical works are original commentaries, apocryphal works, workbooks, books of prayers, Confucian works, Taoist works, Nestorian Christian works, works from the Chinese government, administrative documents, anthologies, glossaries, dictionaries, and calligraphic exercises. Wang sold the majority of them to Aurel Stein for the paltry sum of 220 pounds, a deed which made him notorious to this day in the minds of many Chinese.

Rumors of this discovery brought several European expeditions to the area by 1910. These included a joint British/Indian group led by Aurel Stein (who took hundreds of copies of the Diamond Sutra because he was unable to read Chinese), a French expedition under Paul Pelliot, a Japanese expedition under Otani Kozui which arrived after the Chinese government's forces[clarification needed] and a Russian expedition under Sergei F. Oldenburg which found the least.

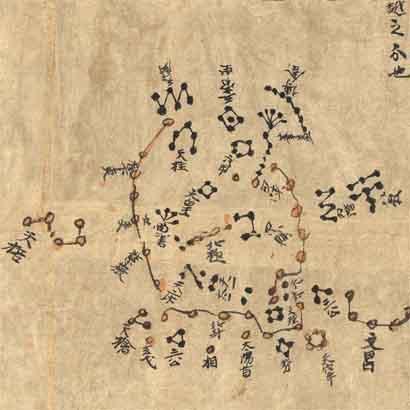

Pelloit was interested in the more unusual and exotic of Wang's manuscripts such as those dealing with the administration and financing of the monastery and associated lay men's groups. These manuscripts survived only because they formed a type of palimpsest in which the Buddhist texts (the target of the preservation effort) were written on the opposite side of the paper. The remaining Chinese manuscripts were sent to Peking (Beijing) at the order of the Chinese government. Wang embarked on an ambitious refurbishment of the temples, funded in part by solicited donations from neighboring towns and in part by donations from Stein and Pelliot. The image of the Chinese astronomy Dunhuang map is one of the many important artifact found on the scrolls.

Today, the site is the subject of an ongoing archaeological project. The Mogao Caves became one of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1987.

Northern end of the Mogao cliff face, pitted with caves for shelter

A Tang Dynasty inscription records that the first cave in the Mogao Grottoes was made in 366 A.D. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) listed the Mogao Grottoes on the World Heritage List in 1987. According to archaeologists, it is the greatest and most consummate repository of Buddhist art in the world.

Despite erosion and man-made destruction, the 492 caves are well preserved, with frescoes covering an area of 45,000 square metres, more than 2,000 colored sculptured figures and five wooden eaves overhanging the caves.

Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara

Heavenly Being

Many pavilions, towers, temples, pagodas, palaces, courtyards, towns and bridges in the murals provide valuable materials for the study of Chinese architecture. Other paintings depict Chinese and foreign musical performances, dancing and acrobatics.

The 'Cave for Preserving Scriptures', was discovered by a Taoist monk Wang Yuanlu in 1900. The cave contains more than 50,000 sutras, documents and paintings covering a period from the 4th to the 11th centuries. It was one of China's most significant archaeological finds. These precious relics are of great historical and scientific value.

Detail from the Procession of Zhang Yichao

Ananova - May 12, 2004

A Chinese star chart possibly dating from the 7th century AD mapped the heavens with an accuracy unsurpassed until the Renaissance, according to research. The Dunhuang chart is the oldest manuscript star map in the world and one of the most valuable treasures in astronomy.

The fine paper scroll, measuring 210 by 25 centimetres, (82 by 10 inches) displays no less than 1,345 stars grouped in 257 non-constellation patterns. Such detail was not matched until Galileo and other European astronomers began searching the skies hundreds of years later - and they had the advantage of telescopes.

The chart includes very faint stars that are extremely difficult to find with the naked eye. It also represents the sky as a sphere projected on a cylinder, a modern technique first adopted in Europe in the 15th century.

The first part of the document consists of a collection of predictions based on shapes of clouds - evidence of the important role divination played in ancient China.

Dr Francoise Praderie, from the Paris Observatory, who studied the map with fellow French astronomer Dr Jean-Marc Bonnet-Bidaud, said: "The origin of the star chart's manufacture and real use remains unknown. One can conjecture that it was used for military and travellers' needs and probably also for uranomancy - divination by consulting the heavens - as suggested by the cloud divination texts preceding the charts. "The long tradition in China of searching the sky for celestial omens has therefore led to an early and unsurpassed precision in star catalogues."

0 comments:

Post a Comment