The first signs of complex society in Mesoamerica are that of the Olmec civilization wh were prominent in Mesoamerica from as early as 1500 BCE through 100 BCE, although there is evidence that the Olmec culture existed into the Common Era.

The Olmec heartland is an area on the south coast of the Gulf of Mexico coastal plain of southern Veracruz and Tabasco, is thus called because of the concentration of a large number of Olmec monuments as well as the greatest Olmec sites.

The area is about 125 miles long and 50 miles wide (200 by 80 km), with the Coatzalcoalcos River system running through the middle. These sites include San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, Laguna de los Cerros, Tres Zapotes, and La Venta is one of the greatest of the Olmec sites.

La Venta is dated to between 1200 BCE through 400 BCE which places the major development of the city in the Middle Formative Period. Located on an island in a coastal swamp overlooking the then-active Río Palma river, the city of La Venta probably controlled a region between the Mezcalapa and Coatzacoalcos rivers.

The site itself is about 18 miles inland with the island consisting of slightly more than 2 square miles of dry land. The main part of the site is a complex of clay constructions stretched out for 12 miles in a North-South direction, although the site is 8° West of true North.

The entire southern end of the site is covered by a petroleum refinery, and has been largely demolished, making excavations difficult or impossible. Many of the site's monuments are now on display in the archaeological museum and park in the city of Villahermosa, Tabasco.

The Olmec heartland is characterized by swampy lowlands punctuated by low hill ridges and volcanoes. The Tuxtla Mountains rise sharply in the north, along the Bay of Campeche. Here the Olmecs constructed permanent city-temple complexes at several locations, among them San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, La Venta, Tres Zapotes, Laguna de los Cerros, and La Mojarra.

They also had great influence beyond the heartland: from Chalcatzingo, far to the west in the highlands of Mexico, to Izapa, on the Pacific coast near what is now Guatemala, Olmec goods have been found throughout Mesoamerica during this period.

The Olmec domain extended from the Tuxtlas mountains in the west to the lowlands of the Chontalpa in the east, a region with significant variations in geology and ecology. Over 170 Olmec monuments have been found within the area, and eighty percent of those occur at the three largest Olmec centers, La Venta, Tabasco (38%), San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan, Veracruz (30%), and Laguna de los Cerros, Veracruz (12%).

Those three major Olmec centers are spaced from east to west across the domain so that each center could exploit, control, and provide a distinct set of natural resources valuable to the overall Olmec economy. La Venta, the eastern center, is near the rich estuaries of the coast, and also could have provided cacao, rubber, and salt. San Lorenzo, at the center of the Olmec domain, controlled the vast flood plain area of Coatzacoalcos basin and riverline trade routes.

Laguna de los Cerros, adjacent to the Tuxtlas mountains, is positioned near important sources of basalt, a stone needed to manufacture manos, metates, and monuments. Perhaps marriage alliances between Olmec centers helped maintain such an exchange network.

Until the early 1900's, the Maya civilization was considered to be the parent culture in Mesoamerica from which all other societies sprouted. There have been many Mayan sculptures and carvings found in the region, so all other carvings were also considered to be that of the Maya. One difference in the carving is that some carvings of large heads had faces with more African looking features than many of the other Mayan works.

There was also evidence of a half-jaguar half-man beast, which also did not fit in with other Mayan finds. It wasn't until 1929, when Marshall H Saville, the Director of the Museum of American Indian in New York, classified these new works as an entirely new culture not of Mayan heritage. He named this culture Olmec, which means the "rubber people" in Nahuatl, the language of the Mexica ("Aztec") people. It was the Aztec name for the people who lived in this area at the much later time of Aztec dominance. Ancient Mesoamericans, spanning from ancient Olmecs to Aztecs, extracted latex from Castilla elastica, a type of rubber tree in the area. The juice of a local vine, Ipomoea alba, was then mixed with this latex to create rubber as early as 1600 BC.

It is not known what name the ancient Olmec used for themselves. Later Mesoamerican accounts seem to refer to the ancient Olmec as "Tamoanchan".

The oldest Olmec site originated at its base in San Lorenzo, Tenochtitlan, where distinctively Olmec features begin to emerge around 1150 BC. The rise of civilization here was probably assisted by the local ecology of well watered rich alluvial soil, encouraging high maize production. This ecology may be compared to that of other ancient civilizations: Mesopotamia and the Nile River Valley.

At its height, this village had a population of less than 1,000 people. The inhabitants were farmers and fishermen who also did a small amount of hunting. The major crops were maize, beans, and squash. The fishing season coincided with the flooding of the river. The men would catch fish in landlocked ponds after the flooding of the river subsided. Along with fish, the Olmec would catch turtles for their main source of protein. If the fishing was slow and the turtle hunting was not going well, the Olmec would substitute domesticated dog and turkey meat in their diet.

It is speculated that the dense population concentration at San Lorenzo encouraged the rise of an elite class that eventually ensured Olmec dominance and provided the social basis for the production of the symbolic and sophisticated luxury artifacts that define Olmec culture.

Evidence of materials in San Lorenzo that must have come from distant locations suggests that early Olmec elites had access to an extensive trading network in Central America. This wwa most likely be protected by some sort of military system.

It is not known with any clarity what happened to this culture. Their main center at San Lorenzo, was all but abandoned around 900 BC, and La Venta became the main city. Environmental changes may have been responsible for this move, with certain important rivers changing course. However, there is also some evidence suggestive of an invasion and destruction of Olmec artifacts around this time.

Around 400 BC, La Venta also came to an end, although the importance of the ceremonial complexes apparently outlasted the Olmec state or culture. Within a few hundred years of the abandonment of their last cities, successor cultures had become firmly established in their former lands, most notably the Maya to the east, the Zapotec to the southwest, and the Teotihuacan culture to the west.

The great Olmec centers that soon developed at La Venta, San Lorenzo, and Laguna de los Cerros, and the smaller centers such as Tres Zapotes, were not simply vacant religious sites, but dynamic settlements that included artisans and farmers, as well as religious specialists and the rulers.

The Olmec architecture at San Lorenzo, for example, includes both public-ceremonial buildings, elite residences, and the houses of commoners. Olmec public-ceremonial buildings were most typically earthen platform mounds, some of which had larger house-like structures built upon them.

At La Venta we can see that after 900 BC such platform mounds were arranged around large plaza areas and include a new type of architecture, a tall pyramid mound.

An important feature at the Olmec centers were drainage systems consisiting of a buried network of stone drain lines, long U-shaped rectangular blocks of basalt laid end to end and covered with capstones. Research at San Lorenzo suggests those systems were actually aqueducts used to provide drinking water to the different areas of the settlement. Some of the aqueduct stones, such as San Lorenzo Monument 52, were also monuments, indicating that the aqueduct system had a sacred character as well.

The word "Olmec" also refers to the rubber balls used for their ancient ball game. Early modern explorers applied the name "Olmec" to the rediscovered ruins and art from this area before it was understood that these had been already abandoned more than a thousand years before the time of the people the Aztecs knew as the Olmec.

Rubber ball games have great antiquity throughout the Americas, and the recent discovery of several rubber balls at the Olmec site of El Manati, near San Lorenzo, confirms that the game was played by the Olmec. Archaeologists working at La Venta twenty years ago discovered what they hypothesized were the remains of a ball court there, and it is possible that such ball courts were also part of the architecture at Olmec centers.

The Olmec were perhaps the originators of the Mesoamerican ballgame, prevalent among later cultures of the region and used for recreational and religious purposes. They were playing ball before anyone else has been documented doing so.

There is a general consensus that the Olmec spoke a language in the Mixe-Zoquean family, although the evidence is limited.

The Olmec may have been the first Mesoamericans to develop a writing system, but no examples of it have yet been found. At the present time, there is some debate as to whether or not symbols found in 2002 dated to 650 BC are actually a form of Olmec writing preceding the oldest Zapotec writing dated to about 500 BC.

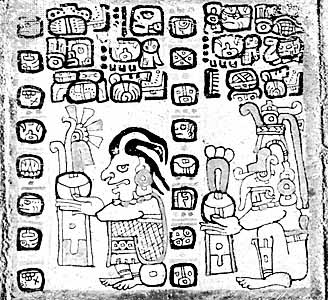

There are other later hieroglyphs known as "Epi-Olmec". "Epi-Olmec" means "post Olmec", and while there are some who believe that Epi-Olmec may represent a transitional script between an earlier, unknown Olmec writing system and Maya writing, the matter is for the time being unsettled. Epi-Olmec Script

The Olmec writing system is unique. The Signs are similar to the writing used by the Vai people of West Africa. The Olmecs spoke and aspect of the Manding (Malinke-Bambara) language spoken in West Africa.

Both the Olmec and epi-Olmec had hieroglyphic writing systems. Olmec is a syllabic writing system used in the Olmec heartland from 900 BC- AD 450.

The Olmec people introduced writing to the New World. The Olmec script is a logosyllabic script. The Olmec had both a syllabic and hieroglyphic script. The hieroglyphic signs were simply Olmec syllabic signs used to make pictures. There are two forms of Olmec hieroglyphic writing : the pure hieroglyphics ( or picture signs); and the phonetic hieroglyphics, which are a combination of syllabic and logographic signs.

The decipherment of the Olmec writing of ancient Mexico provides us with keen insight into the world of the Olmec.

Scholars have long recognized that the Olmecs engraved many symbols or signs on pottery, statuettes, batons/scepters, stelas and bas reliefs that have been recognized as a possible form of writing.

Rafinesque (1832) published an important paper on the Mayan writing that helped in the decipherment of the Olmec Writing. In this paper he discussed the fact that when the Mayan glyphs were broken down into their constituent parts, they were analogous to the ancient Libyco-Berber writing.

The Libyco-Berber writing can not be read in either Berber or Taurag, even though these people use an alphabetic script similar to the Libyco-Berber script which is syllabic CV and CVC in structure.

This was an important article because it offered the possibility that the Mayan signs could be read by comparing them to the Libyco-Berber symbols (Rafineque, 1832). This was not a farfetched idea, because we know for a fact that the cuneiform writing was used to write four different languages: Sumerian, Hittite, Assyrian and Akkadian.

The late Olmec had already begun to use a true zero (a shell glyph) several centuries before Ptolemy, possibly by the fourth century BC. This would later become an integral part of Maya numerals.

The Olmecs were clever mathematicians and astronomers who made accurate calendars.

The Epi-Olmec who unhabited the same land, and were probably descended at least in part from the Olmec, seem to have been the earliest users of the 'bar and dot' system of recording time.

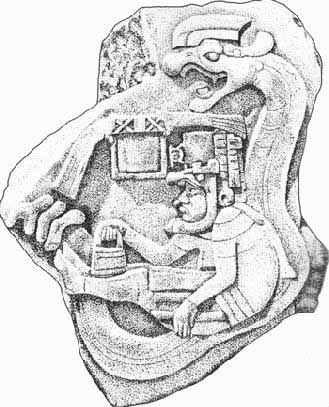

Detail of Long Count Date

The low relief on this stone shows the detail from a four-digit numerical recording, read as 15.6.16.18. The vigesimal (or base-20) counting system has been used across Mesoamerica. A value of 5 is represented by a bar, and a value of 1 is represented by a dot, such that the three bars and single dot here stands for 16. The Maya would later adopt this counting system for their Long Count calendar.

In 1939, an excavation of an Olmec site found a stela, which changed all views on the Maya being the oldest civilization. One side had Olmec carvings while the other showed a row of dots and bars, believed to be a dating method. According to the numbers on the stela, the Olmec had recorded a date almost 300 years earlier than that of the earliest Mayan carved monument. The date in this relief, the oldest recorded date in Mesoamerica, correspondes to a day in the year 31 BC.

Olmec artforms emphasize both monumental statuary and small jade carvings and jewelry. Much Olmec art is highly stylized and uses an iconography reflective of the religious meaning of the artworks.

Some Olmec art, however, is surprisingly naturalistic, displaying an accuracy of depiction of human anatomy perhaps equaled in the Pre-Columbian New World only by the best Maya Classic era art.

Common motifs include downturned mouths and slit-like slanting eyes, both of which can be seen in most representations of "were-jaguars" or jaquar gods. Cat Headed Beings

In addition to human subjects, Olmec artisans were adept at animal portrayals, for example, this ceramic ancient Olmec "Bird Vessel", dating to circa 1000 BC. Ceramics are produced in kilns capable of exceeding approximately 900° C. The only other prehistoric culture known to have achieved such high temperatures is that of Ancient Egypt. Bird Headed Beings and Thoth

Pottery

In March 2005, a team of archaeologists used NAA (neutron activation analysis) to compare over 1000 ancient Mesoamerican Olmec-style ceramic artifacts with 275 samples of clay so as to "fingerprint" pottery origination. They found that "the Olmec packaged and exported their beliefs throughout the region in the form of specialized ceramic designs and forms, which quickly became hallmarks of elite status in various regions of ancient Mexico.

In August 2005 another study, this time using petrography, found that the "exchanges of vessels between highland and lowland chiefly centers were reciprocal, or two way." Five of the samples dug up in San Lorenzo were "unambiguously" from Oaxaca. According to one of the archaeologists conducting the study, this "contradicts recent claims that the Gulf Coast was the sole source of pottery" in Mesoamerica.

The results of the INAA study were later defended in March 2006 in two articles in Latin American Antiquity. Because the INAA sample is much larger than the petrographic sample (a total of over 1600 analyses of raw materials and clays vs. approximately 20 pottery thin sections in the petrographic study), the authors of the Latin American Antiquity papers argue that the petrographic study cannot possibly overturn the INAA study.

"The Grandmother", Monument 5 at La Venta

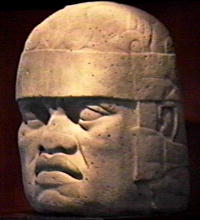

Perhaps the best-recognized Olmec art are the enormous helmeted heads. There have been 17 colossal heads unearthed to date.

No known pre-Columbian text explains these impressive monuments that have been the subject of much speculation. Given the individuality of each, these heads seem to be portraits of famous ball players or perhaps kings rigged out in the accoutrements of the game. The unique elements in the headgear can also be recognized in headdresses of human figures on other Gulf Coast monuments, suggesting that these are personal or group symbols.

The heads range in size from the Rancho La Corbata head, at 3.4 m high, to the pair at Tres Zapotes, at 1.47 m. Some sources estimate that the largest weighs as much as 40 tons, although most reports place the larger heads at 20 tons.

Colossal Head found at La Venta, approximately 6 feet tall and 5 feet across.

The heads were carved from single blocks or boulders of volcanic basalt, quarried in the Tuxtla Mountains. It is likely that the heads were carried on large balsa rafts from the Llano del Jicaro quarry to their final locations. To reach La Venta, roughly 80 km (50 miles) away, the rafts would have had to move out onto choppy waters of the Bay of Campeche.

Some of the heads, and many other monuments, have been variously mutilated, buried and disinterred, reset in new locations and/or reburied. Whether these actions were undertaken as a ritual or as a result of a conflict or conflicts is yet to be decided.

Almost all of these colossal heads bear the same features, flattened nose, wide lips, and capping headpiece, possible features of the Olmec warrior-kings. Often carved from volcanic stone at the stone's source, these heads would be rafted to the centers of the major Olmec cities along the southern Gulf of Mexico coast. Of the 9 heads catalogued from the ruins of San Lorenzo in southern Veracruz state, this is referred to as San Lorenzo 6.

In 1862 a colossal stone head was discovered in the state of Veracruz along the steaming Gulf Coast of Mexico. In the years to come, artifacts from the culture later termed Olmec turned up at widespread sites in Mexico and adjacent Central America, with the greatest number of characteristic themes being present in the region of the original discovery.

Monuments were also an important characteristic of Olmec centers. Today they provide us with some idea of the nature of Olmec ideology. The colossal heads are commanding portraits of individual Olmec rulers, and the large symbol displayed on the 'helmet' of each colossal head appears to be an identification motif for that person.

Colossal heads glorified the rulers while they were alive, and commemorated them as revered ancestors after their death.

Altars were actually the thrones of Olmec rulers. The carving on the front of the throne shows the identified ruler sitting in a niche that symbolizes a cave entrance to the supernatural powers of the underworld. That scene communicated to the people their ruler's association with cosmological power.

The magnificent colossal stone heads, massive altars, and sophisticated anthropomorphic and zoomorphic statues found at Olmec sites in southern Veracruz and Tabasco, are the oldest known monuments in Prehispanic Mexico.

In 1939 a carving was discovered near the gigantic head with a characteristic Olmec design on one side and a date symbol on the other. This revealed a shocking truth: the Olmecs had a far greater right to be considered the mother culture. Hundreds of years earlier than anyone had imagined, simple villages had given way to a complex society governed by kings and priests, with impressive ceremonial centers and artworks. Today many find the term "mother culture" misleading, but clearly the Olmecs came first.

Other megalithic heads were discovered in the intervening years, all with African facial features. This is not necessarily to suggest that the founders or leaders of Olmec civilization came directly from Africa, since many original populations of countries like Cambodia and the Philippines have similar characteristics. These might have been brought along when the first humans entered the Americas from Asia.

At La Venta, Stirling and Philip Drucker, began excavations in a plaza area, Complex A, on the north side of La Venta's 32 meter-tall (106 ft.) earthen pyramid mound. They soon made astonishing discoveries. Their trenches uncovered caches of polished jade celts, colored clay floors, and several royal burials. One burial was in a large sandstone sarcophagus carved to depict a supernatural caiman. Two other burials occurred in a tomb chamber constructed from basalt columns. All the burials included offerings of beautiful greenstone figures, jewelry, and celts.

When Stirling presented his discoveries at the meeting, held by the Mexican Society of Anthropology (Sociedad Mexicana de Antropologia) at Tuxtla Gutierrez in 1942, disagreements immediately arose over the dating of La Venta and the Olmec.

Drucker believed that La Venta was contemporaneous with Classic period Maya civilization, while Alfonso Caso and Miguel Covarrubias eloquently argued that the Olmec precede the Maya and Mexico's other great civilizations. Stirling agreed with Caso and Covarrubias. Because the meeting had raised so many questions about the Olmec, historian Wigberto Jimenez Moreno wrote that same year about "El enigma de los olmecas." It took another 15 years to resolve the question of the antiquity of the Olmec.

In 1957 the first radiocarbon dates from La Venta, 800-400 B.C., proved Caso, Covarrubias, and Stirling to be correct, and recent research and radiocarbon dating now places the time range of the Olmec from 1200 to 1500 B.C. Today the forest is gone at La Venta and a large Pemex refinery is located near the site, but archaeologists now have a clearer understanding of the Olmec. The Olmec no longer seem as enigmatic as they did in 1942.

Much of the Olmec monumental art is found damaged and mutilated. The portrait statues of rulers are decapitated, and massive fragments are missing from the corners of altars. Only the colossal portrait heads survived relatively unharmed. Although that damage was once blamed on invaders or internal revolutions, it was an action that occurred repeatedly throughout the 700 years that the Olmec created monuments. Therefore, most scholars now believe that monument mutilation was carried out by the Olmec themselves for sacred or ritual reasons. Perhaps when a ruler died his monuments were destroyed. New evidence indicates that some monuments were broken and the pieces recarved to make other monuments.

It is now known that two colossal stone heads from San Lorenzo had originally been large rectangular altars that were later resculpted into colossal heads. When a ruler died, was he venerated by converting his throne into his colossal portrait head.

Geologists have determined that the basalt used to make most of the monuments at San Lorenzo and La Venta came from the area of the Tuxtlas mountains. In 1960, archaeologist Alfonso Medellin Zenil discovered Llano del Jicaro, an Olmec basalt quarry site and monument workshop. The quarry, near the Tuxtla mountains, is only 7 kilometers (4 miles) from the Olmec center of Laguna de los Cerros, and was controlled by it. Excavations at Llano del Jicaro in 1991 provided data on the process of monument manufacture. A large unfinished altar there demonstrates that the monuments were given their basic shape at the quarry site, and then transported to the centers for finishing.

Although archaeology has answered many questions about the Olmec, many more still remain. Research has concentrated primarily on the centers of San Lorenzo and La Venta, and very little is known about Laguna de los Cerros, or smaller Olmec centers, or Olmec life in small farming hamlets. We also have very little archaeological information about the 500-300 B.C. time period in southern Veracruz and Tabasco and, therefore, we do not know how the Olmec culture ended. San Lorenzo and La Venta declined in importance, perhaps due to major change in the river systems that helped support those centers. However, in the northern area of the Olmec domain there was some cultural continuity long after 500 B.C. Tres Zapotes became an important post-Olmec center, and Laguna de los Cerros continued as a major center into the Classic period.

Jaguar Child

The most well-known aspect of shamanism in Mesoamerican religion, and in the whole of Native American shamanism, is the ability to assume the powers of animals associated with the shaman. Such animals are called nahuales, and in Olmec art the most common of these is the jaguar. In a sense, the optimal spirit would have the spirituality and intellect of man and the ferocity and strength of the jaguar, these are all combined in the shaman and his jaguar nahuale. The Jaguar Child may exemplify this combination. This is a very common representation in Olmec art, and it often includes the slitted eyes and curved mouth pronounced in this close-up.

Eagle Spirit

The slitted eyes and curved mouth are also shown in this small carving, so the human presence is felt here. The eyebrows are feathered like an eagle's brows, this figure may show the way the shaman's soul traverses the heavens with the power of the eagle's flight. From the shaman's perspective, the soul requires an animal medium, the nahual, to enter the various realms: the heavens, the earth, and the underworld. Notice the cinnabar tracing etched into the face; this mercury ore was a precious mineral for the Olmecs.

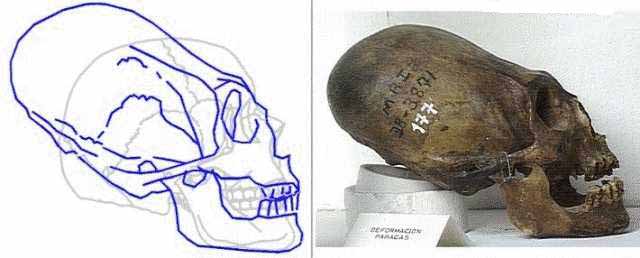

The small figures in this scene have been restored to the original positions they had been found in at La Venta, Tabasco. There is no definite answer for what this scene is enacting. One of the noteworthy aspects of this concession is that all of the men have elongated skulls, the result of cranial deformation begun at an early age. For the Maya, this would be a practice reserved for noble children.

Mud Men from the Popul Vuh Story of Creation

Crystal Skulls

The mythology of the Olmec people significantly influenced the social development and mythological world view of Mesoamerica. As there is no surviving direct account of Olmec religious belief, much remains unknown on the subject. None the less, some observations can be made, mostly based on surviving art and archeology, and by comparison to later, better documented, peoples of Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica whose religious art uses similar motifs.

The height of Olmec culture, generally centered in the modern Mexican state of Veracruz, is currently dated from 1200 BCE to about 800 BCE. The Olmec continued well beyond this period, establishing monuments and communities until 400 BCE. Some scholars assert the Olmec existed as a distinct people until nearly 100 BCE. The Olmec developed a hieroglyphic script for their language, the earliest known example dating from 650 BCE.

However surviving Olmec texts are few and the meaning of many of their glyphs remains obscure compared to the much more plentiful and better understood later Maya hieroglyphics or even compared to the Epi-Olmec script. Archaeologists believe that the Olmec and their culture were ancestral to later Mesoamerican peoples, including the Maya civilization, the inhabitants of the city of Teotihuacan, and the modern Mayan speaking groups. Others, including the Toltec and the Aztec, may not have descended from the Olmecs but were heavily influenced by their culture.

One of the best known middle to late Olmec sites, La Venta in the state of Tabasco, contains representations of several apparently mythological figures. These representations, generally dating from 800 to 400 BCE, include a feathered serpent, a man of crops with corn growing out of his head, and a rain spirit in the guise of a dwarf or child. Similar images are frequently found in the myths of later cultures in the area.

Olmec mythology has left no documents comparable to the Popul Vuh from Maya mythology, and therefore any exposition of Olmec mythology must rely on interpretations of surviving monumental and portable art and comparisons with other Mesoamerican mythologies. Olmec art shows that such deities as the Feathered Serpent and the Rain Spirit were already in the Mesoamerican pantheon in Olmec times.

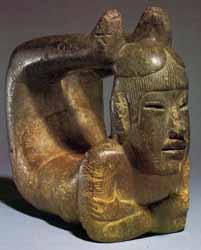

Olmec Ruler or God connected physical and spiritual worlds. His pose represents his means to link with the supernatural worlds. The turned down mouth, a feline feature, suggests that the human ruler was aided by a power animal such as a cat, jacquar, traditionally the spirit campanion of shamans and kings.

It was formerly thought that the Olmec worshiped only one god, a rain deity depicted as a 'were-jaguar', but study has shown that there were at least 10 distinct gods represented in Olmec art.

Present were several important deities of the later, established Meso-American pantheon, such as the fire god, rain god, corn/maize god, and the Feathered Serpent.

The Man of Crops is a fertility figure in Mesoamerican mythology. Among the Olmec, gods are often depicted with a distinct cleft on the forehead, perhaps identifying this characteristic as divine. A carved celt from Veracruz shows a representation of God II, or the Maize God, growing corn from his cleft, and also shows this god with the snarling face associated with the jaguar (Coe 1972:3).

The Man of Crops was a human man or boy who chose to give his life so that his people might grow food. The heroic Man of Crops is sometimes mentored or assisted by a god figure from the other world.

The myths of the Popoluca people of Veracruz make him a tribal hero, sometimes called Homshuk, whose death gives food to all mankind. This hero names himself as "he who sprouts at the knees."

In Aztec, Tepecano, and Tarascan versions, he is buried and corn or tobacco grows from his grave.

A myth of the Christianized Quiche states that, during and following his crucifixion, corn and other crops spilled from the body of Jesus.

Some people believe that the principal deity was fundamentally an Earth god, though his power was not limited to terrestrial matters, and took the form of a jaguar. This God could have a water-earth persona. As a jaguar encompassing the forces of life or at least a dominance in its two strongest categories (with regards to Olmec life), water and earth. This deity supposedly had dominance over all things terrestrial and celestial.

This God may have been half-jaguar, half-serpent, "were-jaguars". The jaguar represents the Earth Mother with the serpent representing the water, thus combining to represent life.

The Olmec image of the rain spirit appears frequently in the mythology of succeeding cultures. Invariably the rain spirit is male, though he may have a wife who shares authority over the waters. Often he is perceived as a child or a young man, sometimes as a dwarf. He may also be portrayed as a powerful rain god, with many helpers.

In Aztec and Maya traditions, the rain lord is a master spirit, attended by several helpers. His name in the Aztec language is Tlaloc, and his helpers are "tlaloque."

The Maya of the Yucatan recognize Chaac and the "chacs." In the Guatemalan area, these spirits are often associated with gods of thunder and lightning as well as with rain.

The rain spirits are known as Mam and the "mams" among the Mopan of Belize. In some traditions, as with the Pipil of El Salvador, the figure of the master is missing, and the myths focus on "rain children," or "rain boys."

Modern Nahua consider these numerous spirits to be dwarfs, or "little people." In the state of Chiapas, the Zoque people report that the rain spirits are very old but look like boys.

The mythological figure of the feathered or plumed serpent depicted throughout North America and Mesoamerica probably originated in Olmec times. In later traditions the Quetzal Feathered Serpent deity was known as the inventor of books and the calendar, the giver of maize corn to mankind, and sometime as a symbol of death and resurrection, often associated with the planet Venus. The Maya knew him as Kukulkán; the Quiché as Gukumatz. The Toltecs portrayed the plumed serpent as Quetzalcoatl, the rival of Tezcatlipoca. Art and iconography clearly demonstrate the importance of the Feathered Serpent Deity in Classic era as well as Olmec art.

Other aspects of mental culture are less well-known; some Olmec jades and a monument from La Venta have non-calendrical hieroglyphs, but none of this writing has been deciphered.

The Olmecs are believed to be one of the first tribes to engage in Shamanistic rituals. In the Olmec civilization the reoccurring motif of the 'Were-jaguar' can be seen in many statuettes and carvings. It is believed that the Olmecs were a kind of "mother culture" which directly gave rise to all subsequent major civilisations and this is how Shamanism first spread.

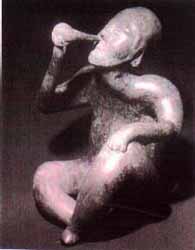

The Olmecs are said to have been ancestors of the Jaquar. The Olmec Tribe believed that the Jaquar was a rain deity and fertility diety. The Jaquar was chosen because the Olmecs believed it was the most powerful and feared animal. They also believed that the Jaquar was an Avatar of the living and the dead. The men would sacrifice blood to the jaguar, wear masks, dance, and crack whips to imitate the sound of thunder. This ritual was done in May. The Olmec also made offerings of jade figures to the jaguar. The Olmecs made numerous statues representing "Were, Jaquar " men. These men are normally shown with grimacing Jaquar facial features with Human bodies. They are believed to be men , of the Olmec tribe, that are transforming into the Jaquar. One of these transforming Shamans can be seen in the statue "Crouching figure of a Man-Jaquar".

It is an almost black, little figurine of a man rising from one knee in the ecstasy of transformation. The transformation figure shows the human and feline characteristics brilliantly fused together. The head and ears remain human , but the crown of it¹s head is smooth , as if shaved. The features of it's face seem to flow into each other and the eye sockets are wide and deeply bored. Extended by incised lines above the eyes, the carved eyebrows are similar to flame eyebrows and signify the shedding of skin.

In the figurine the 'Standing figure of a Were-Jaquar' another Shaman is seen in the transformation process . This figure stands with one leg forward to counterbalance the slight torsion of the body. The arms are extended and each hand is balled into a fist, similar to a boxing stance. This Figure has almost the exact same features as the 'Crouching Figure' that represent the ecstasy of the transformation. Its hands and feet are oversized to anticipate the paws of the Jaquar.

In both figures the tortured facial features are intended to convey, not ferocity and aggressiveness, but emotional stress beyond endurance. It is precisely the sort of physically and mentally exhausting crisis, the crossing of the threshold between two worlds, to kinds of reality, if you will, that is part and practice of ecstatic Shamanism everywhere. The crossing over and transformation into the most powerful predator of the rain forest and the Savannah.

The Transformation was brought on by a series of activities which could incorporate singing or chanting to the Jaguar deity. The Shaman would dance around and chant a mantra to spirit world and would also use the rhythm of a beating. It is also believed that the Olmec would also ingest a 'mind altering' drug which would intoxicate the Shaman and make him dizzy Tobacco powder , which was also used to achieve the transformation could be inhaled directly through the nose or ground up with lime to make a chewing wad. The evidence to support this can be seen in the Hollow Figure in this statue a man is seen using a snuffing pipe made from small gourds.

The "were-jaguar " Shamans were also associated and depicted in acrobatic poses, this represents the agility of the feline. Shamans were believed to have the ability to flip backwards and transform before they had landed. There have been a number a figures found , that incorporate acrobatic poses. In the statues 'Figure with feet on head' and "vessel in the form of a contortionist". Shamans are shown in complex and complicated poses. The Shamans seems to very comfortable and achieve each pose with ease.

The Olmec believed in chaneques or dwarf trickters who

lived in water falls. They had their own beliefs in cosmology.

World Tree, Tree of Life

Olmec Glyph 900-500 BC: Dallas Museum

About 3,000 years ago, elders and leaders in farming communities of Mesoamerica established a shared vision of their world. These sages of Olmec civilization etched their creed on polished stone artifacts and then rubbed red paint into the patterns. This is a code that could be read by any sage who knew the religion. This plaque reords the story of creation. It shows the World Tree sprouting out of Creation Mountain at the Three-Stone-Place the center of the night sky, the renewed sky, the mountian and the renewed earth, and the Three-Stone-Place the hearth, the place of First Father's rebirth as Maize.

It confirms the tradition recorded by:

- Friar Diego de Landa that the Olmec people made twelve migrations to the New World.

- Famous Mayan historian Ixtlixochitl, that the Olmec came to Mexico in "ships of barks " and landed at Pontochan, which they commenced to populate

(Metaphors: Sea=Collective Unconscious or consciousness grids of our virtual reality experience. 12 = 12 Around 1.)

Another Version of the Tree of Life

The Eye of Creation and the Snake or Human DNA

God/Trickster connected to the serpent rattlesnake, DNA, Quetzalcoatl and 2012

Container, Vessel, Flow of the Collective Unconsciousness, Grids

Return to Zero Point at the Time of the Aquarian Age, Water Bearers

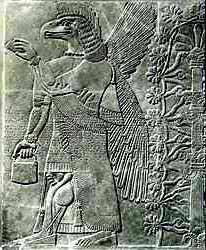

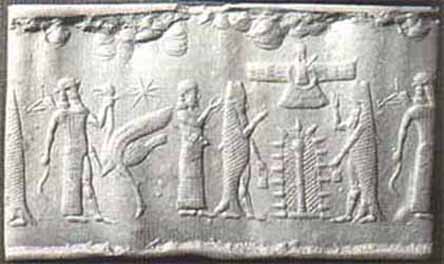

This is reminiscent of Winged Reptilian Gods of

Sumer , Mesopotamia, Persia/Iraq , the Cradle of Civilization

Anunnaki, Ea and Enki, Nibiru

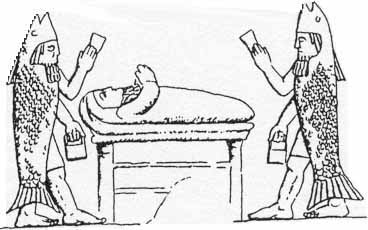

Ea stands in his watery home the Apsu.

Enki walks out of the water to the land.

Lion, Symbol of Zoroaster, Age of Leo

Handing the water/liquidblood of life, to a bio-genetically engineered human

Creation of Bloodlines, Alchemy of Humanity, Time through Consciousness

Male-female separation of Twin Soul Aspects Reunited, 2012

Amphibious Gods, Oannes, Oneness, Babylon, Baby Lion

Aquatic, Enki, Sumer, Zoroaster above Tree of Life, Persia

Zoroaster as the Faravahar

holding an open circle, Omega, Closure, Leo

References:

Bierhorst, John. The Mythology of Mexico and Central America, William Morrow (1990). ISBN 0-688-11280-3.

Coe, M.D. Olmec Jaguars and Olmec Kings. In E.P. Benson (ed), The Cult of the Feline. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks (1972): pp. 1-12.

Coe, M.D. Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. London: Thames and Hudson (2002): pp. 64, 75-76.

Luckert, Karl W. Olmec Religion: A Key to Middle America and Beyond. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, (1976).

Wikipedia

Crystalinks

Olmecs in the News ...

Quetzalcoatl

Reuters - September 24, 2007

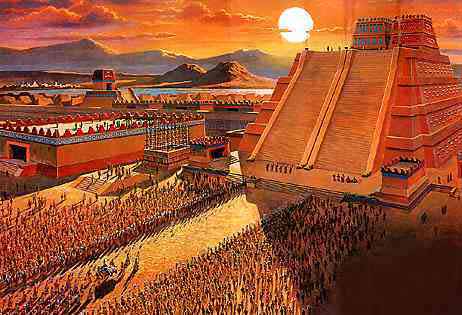

Ancient Mexicans and Egyptians who never met and lived centuries and thousands of miles apart both worshiped feathered-serpent deities, built pyramids and developed a 365-day calendar, a new exhibition shows. Billed as the world's largest temporary archeological showcase, Mexican archeologists have brought treasures from ancient Egypt to display alongside the great indigenous civilizations of Mexico for the first time.

The exhibition, which boasts a five-tonne, 3,000-year-old sculpture of Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II and stone carvings from Mexican pyramid at Chichen Itza, aims to show many of the similarities of two complex worlds both conquered by Europeans in invasions 1,500 years apart. "There are huge cultural parallels between ancient Egypt and Mexico in religion, astronomy, architecture and the arts. They deserve to be appreciated together," said exhibition organizer Gina Ulloa, who spent almost three years preparing the 35,520 square-feet (3,300 meter-square) display.

The exhibition, which opened at the weekend in the northern Mexican city of Monterrey, shows how Mexican civilizations worshiped the feathered snake god Quetzalcoatl from about 1,200 BC to 1521, when the Spanish conquered the Aztecs.

From 3,000 BC onward Egyptians often portrayed their gods, including the Goddess of the Pharaohs Isis, in art and sculpture as serpents with wings or feathers. The feathered serpent and the serpent alongside a deity signifies the duality of human existence, at once in touch with water and earth, the serpent, and the heavens, the feathers of a bird," said Ulloa. Egyptian sculptures at the exhibition -- flown to Mexico from ancient temples along the Nile and from museums in Cairo, Luxor and Alexandria - show how Isis' son Horus was often represented with winged arms and accompanied by serpents. Cleopatra, the last Egyptian queen before the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC, saw herself as Isis and wore a gold serpent in her headpiece.

Uncanny Similarities

In the arts, Mexico's earliest civilization, the Olmecs, echo Egypt's finest sculptures. Olmec artists carved large man-jaguar warriors that are similar to the Egyptian sphinxes on display showing lions with the heads of gods or kings. The seated statue of an Egyptian scribe carved between 2465 and 2323 BC shows stonework and attention to detail that parallels a seated stone sculpture of an Olmec lord. There is no evidence the Olmecs and Egyptians ever met.

Shared traits run to architecture, with Egyptians building pyramids as royal tombs and the Mayans and Aztecs following suit with pyramids as places of sacrifice to the gods. While there is no room for pyramids at the exhibition -- part of the Universal Forum of Cultures, an international cultural festival held in Barcelona in 2004 -- organizers say it is the first time many of pieces have left Egypt. They include entire archways from Nile temples, a bracelet worn by Ramses II and sarcophagi used by the pharaohs. Mexico has also brought together Aztec, Mayan and Olmec pieces from across the country.

Zazacatyl

Ancient City Found in Mexico; Shows Olmec Influence National Geographic, January 26, 2007

A 2,500-year-old city influenced by the Olmecs often referred to as the 'mother culture' of Mesoamerica has been discovered hundreds of miles away from the Olmecs' Gulf coast territory, archaeologists said.

Mexico monolith may cast new light on Mesoamerica

Reuters, May 8, 2006, Mexico City

- A carved monolith unearthed in Mexico may show that the Olmec civilization, one of the oldest in the Americas, was more widespread than thought or that another culture thrived alongside it 3,000 years ago. Findings at the newly excavated Tamtoc archeological site in the north-central state of San Luis Potosi may prompt scholars to rethink a view of Mesoamerican history which holds that its earliest peoples were based in the south of Mexico. "It is a very relevant indicator of an Olmec penetration far to the north, or of the presence of a new group co-existing with the Olmecs," said archeologist Guillermo Ahuja, who led a government team excavating the site for the past five years. Tamtoc, located about 550 miles (885 kilometers) northeast of Mexico City, will open to the public this week, while experts including linguists, historians, ethnographers and others study findings from the site to confirm their origins.

The Olmecs are considered the mother culture of pre-Hispanic Mexico. Ruins of Olmec centers believed to have flourished as early as 1200 B.C. have been found in the Gulf Coast states of Veracruz and Tabasco, with only scattered artifacts found elsewhere. Workers restoring a canal at the site stumbled on the stone monolith. It appears to represent a lunar calendar and contains three human figures and other symbols in relief. "At 25 feet (7.6 meters) long, 13 feet (4 meters) high, 16 inches (40 centimeters) thick and weighing more than 30 tonnes, it may date to as early as 900 BC," Ahuja said. Experts will try to interpret the icons to learn more about the artists and their culture. "They are new symbols in Mesoamerica. At Tamtoc, scientists found evidence of an advanced civilization, with a hydraulic system, canals and other technology, making it the oldest and most advanced center of its time found in what later became Huasteco Indian region," Ahuja said. "It is the first and only Huasteco City we know. The 330-acre (133-hectare) complex has three plazas and more than 70 buildings and may indicate that the Olmecs migrated northward and mingled with other peoples there."

Earliest New World writing revealed, Olmec December 2002, New Scientist

- The discovery of a fist-sized ceramic cylinder and fragments of engraved plaques has pushed back the earliest evidence of writing in the Americas by at least 350 years to 650 BC. Rolling the cylinder printed symbols indicating allegiance to a king, a striking difference from the Old World, where the oldest known writing was used for keeping records by the first accountants. Archaeologists uncovered the cylinder and fingernail-sized fragments among debris from an ancient festival at San Andres, an Olmec town on the coastal plain of the Mexican state of Tabasco. Carbon dating of layers in the rubbish heap gave age of the artefacts.

The next-oldest writing from the region is on a monument at a site of the Zapotec culture 300 kilometres to the west. But its date is poorly constrained, to sometime between 300 BC and 200 AD. Three later cultures in the same area used similar writing, the well-known Mayan, and the lesser-known Isthmain and Oxacan. The cylinder shows two glyphs linked by lines to the mouth of a bird, giving the impression the glyphs are being spoken. One is "ajaw," meaning "king," and the other "three ajaw", a day in the sacred 260-day calendar used throughout the region for over a millennium. Later cultures used similar lines to show speech by people as well as by animals. When covered with ink or paint, the roller printed the bird and symbols on cloth or people's bodies. The date probably was the king's name, a common practice at the time."It's a kind of royal seal, used in decoration," Mary Pohl, an anthropologist at Florida State University in Tallahassee, told New Scientist. People in San Andres probably wore it "to show their fealty to the king" who resided at the main Olmec city of La Venta nearby.

The Olmec were the first American culture with a distinct ruling class, and Pohl believes they developed writing for rituals and rulers. Later Mesoamerican writing retained the links to kings and rituals, including the sacred calendar. Pohl says that writing could have originated at the start of the first Olmec culture in 1300 BC, but no evidence has survived. In contrast, Old World writing is far older and traces back to tokens placed in clay envelopes to keep account of animals or other possessions. By about 3000 BC, symbols written on tablets replaced the tokens, becoming the world's first writing.

Scientists Solve Jade Source Mystery

June 2002, World Scientist

- Since the 18th century, collectors, geologists and archaeologists have sought the answer to a frustrating mystery: The ancient Olmecs fashioned statues out of striking blue-green jade, but the stone itself was nowhere to be found in the Americas. Now scientists believe they have discovered the source, a mother lode of jade in Guatemala that could tell much about ancient American civilizations and about the formation of the continent where they lived. Ever since Alexander von Humboldt began collecting jade in Latin America in the 18th century, Olmec-style statuettes and axes, crafted more than two millennia ago, had been found from Mexico to Costa Rica. But never had that kind of jade been seen naturally in any quantity in the area. Then in 1999, Russell Seitz, a geophysicist who had spent 23 years searching for the source of Olmec jade, took his fiancee to the colonial city of Antigua in central Guatemala. On the roof of a store, he found jade that was vastly different from the opaque jade he had seen in Mexico and Central America, and it was identical to the translucent blue-green stones so coveted by the Olmecs, who lived in central and southern Mexico from 1000-400 B.C.

0 comments:

Post a Comment