The Queen Who Would Be King (1473-1458 BC)

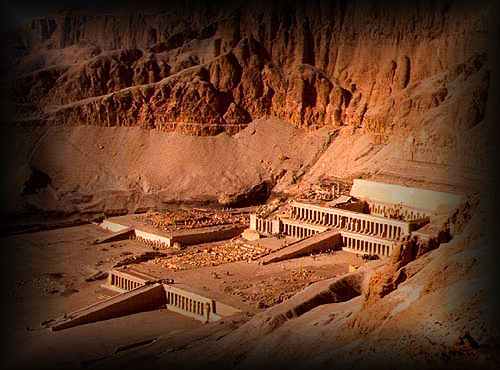

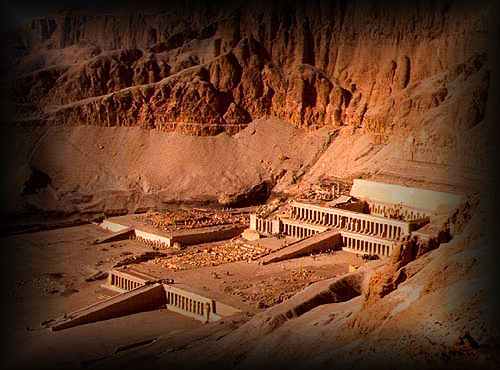

Hatshepsut was the fifth Pharaoh of the18th-dynasty who was one of the handful of female rulers in Ancient Egypt. Her reign was the longest of all the female pharaohs. Her funerary temple still stands as a tribute to her incredible rise to power.

Hatshepsut was the eldest daughter of Thutmose I and Queen Ahmose, the first king and queen of the Thutmosid clan of the 18th Dynasty. Thutmose I and Ahmose are known to have had only one other child, a daughter Akhbetneferu (Neferubity), who died in infancy. Thutmose I also married Mutnofret, possibly a daughter of Ahmose I, and produced several half-brothers to Hatshepsut: Wadjmose, Amenose, Thutmose II, and possibly Ramose, through that union.

Both Wadjmose and Amenose were prepared to succeed their father, but neither lived beyond adolescence. In childhood, Hatshepsut is believed to have been favored by the Temple of Karnak over her two brothers by her father, a view promoted by her own propaganda. Hatshepsut apparently had a close relationship with both her parents, and later produced a propaganda story in which her father Thutmose I supposedly named her as his direct heir (see below) Hatshepsut dressed like a man and wore a false beard to prove that she could be Pharaoh and rule Egypt in her own right.

Hatshepsut was married to her half-brother, Tuthmosis II, with whom she reigned for some 14 years. Realizing his sister-wife's ambitious nature, Tuthmosis II declared his son by the harem girl Isis to be his heir, but when the young Tuthmosis III came to the throne, Hatshepsut became regent and promptly usurped his position as ruler.

To support her cause she claimed the God Amon-Ra spoke, saying "Welcome my sweet daughter, my favorite, the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkare,Hatshepsut. Thou art the King, taking possession of the Two Lands."

She dressed as a king, even wearing a false beard and the Egyptian people seem to have accepted this unprecedented behavior.

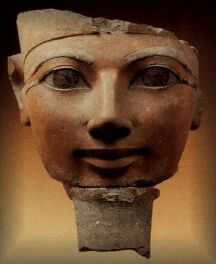

Hatshepsut had herself portrayed in the royal headdress, sometimes as a woman with prominent breasts but more often as male in body as well as costume. Her self-promotion, which extended to a miraculous conception and fictitious coronation in childhood, involved deliberately obscuring the rightful ruler, Tuthmosis III, who was a man by the time he succeeded to unfettered rulership in 1483 BC.

Policies

Upon Thutmose II's death, the throne passed to Thutmose III, and Hatshepsut, as the boy king's aunt and stepmother‹was selected to be interregnum regent until he came of age. At first, it appears that Hatshepsut was patterning herself after the powerful female regents of Egypt's then-recent history, but as Thutmose III approached maturity it became apparent that she had only one model in mind: Sobekneferu, the last monarch of the Twelfth Dynasty, who ruled in her own right. However, Hatshepsut took one step further than Sobekneferu and had herself crowned pharaoh around 1473 BC, taking the throne name Maatkare, meaning "Truth in the soul of the sun." After she ascended the throne she changed her name from the feminine Hatshepsut to the male Hatshepsu.

Hatshepsut surrounded herself with strong and loyal advisors, many of whom are still known today: Hapuseneb, the High Priest of Amun, and her closest advisor, the royal steward Senemut. During her rule, the most powerful, advanced civilization in the world. Because of the close nature of Hatshepsut and Senemut's relationship, some Egyptologists have theorized that they were lovers. Among the evidence they offer to support this claim is the fact that Hatshepsut allowed Senemut to place his name and an image of himself behind one of the main doors in Djeser-Djeseru (a rare and unusual sharing of credit), that Senemut had two tombs constructed near Hatshepsut's tomb (this was, however, a standard privilege for close advisors), and the presence of graffiti in an unfinished tomb, used as a rest house by the workers of her mortuary temple, depicting a male and a hermaphrodite in pharaonic regalia engaging in an explicit sexual act. Although the belief that Hatshepsut and Senemut were lovers is well known, it is highly contested among Egyptologists all that is agreed on is that the steward had ready access to the queen's ear.

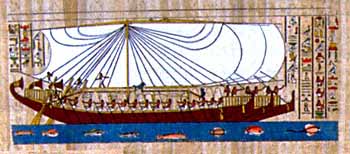

As Hatshepsut reestablished the trade networks that had been disrupted during the Hyksos' occupation of Egypt (the Second Intermediate Period), the wealth of the 18th dynasty that has become so famous since the discovery of the burial of Tutankhamun began to be collected. She oversaw the preparations and funding for a mission to the Land of Punt.

The Egyptians sent trading missions to Punt, a region of East Africa that was rich in gold, resins, ebony, blackwood, ivory and wild animals, including monkeys and baboons. They also went in search of slaves. The best-documented mission was sent during the reign of Hatshepsut. Scenes from these expeditions are illustrated on her funerary temple at Deir el-Bahari, near the Valley of the Kings.

The expedition set out in her name with five ships, each measuring seventy feet (21 m) long, and with several sails; each ship accommodated 210 men, including sailors and thirty rowers. Many goods were bought in Punt, notably myrrh, which is said to have been Hatshepsut's favorite fragrance. Most notably however, the Egyptians returned from the voyage bearing thirty-one live frankincense trees, whose roots were carefully kept in baskets for the duration of the voyage. This was the first ever recorded attempt to replant foreign trees. She reportedly had the trees planted in the courts of her Deir el Bahari mortuary temple. She had the expedition commemorated in relief at Deir el-Bahri, which is famous for its unflattering depiction of the Queen of Punt.

Although many Egyptologists have claimed that her foreign policy was mainly peaceful, there is evidence that she led successful military campaigns in Nubia, the Levant and Syria early in her career.

Hatshepsut was an excellent propagandist, and while all ancient leaders used propaganda to legitimatize their rule, she is one of the most known for it. Much of her propaganda had religious overtones supported by the priests at the Temple of Karnak.

In ancient Egypt, women had a higher status than they did elsewhere in the ancient world, including the court-protected right to own or inherit property. Yet having a female ruler in her own right was rare: only Khent-Kaues, Sobeknefru and possibly Nitocris preceded her as ruling in their own name. Pharaoh was an exclusively male title; at this point in Egyptian history there was no word for a Queen regnant, only one for Queen consort. Hatshepsut is unique in that she was the first woman to take the title of King regnant or King in the absence of a word or title for Queen regnant.

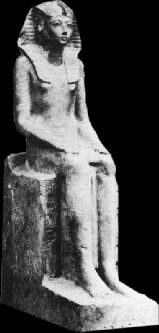

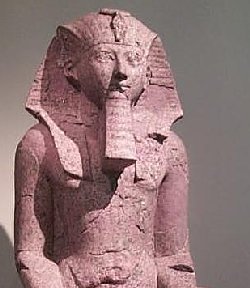

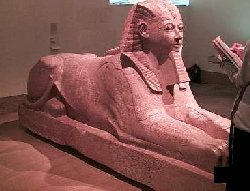

Hatshepsut slowly assumed all of the regalia and symbols of the Pharaonic office: the Khat head cloth, topped with an uraeus, the traditional false beard, and shendyt kilt. Many existing statues show her in both a feminine and masculine form. Statues portraying Sobekneferu also combine elements of traditional male and female iconography and may have served as inspiration for the works commissioned by Hatshepsut.

However, after this period of transition ended, all depictions of her showed her in a masculine form, with all of the pharaonic regalia and with her breasts omitted. Her reasons for doing this are a topic of great debate in Egyptology. The traditional explanation is that her motivation for wearing men's clothing was sexual.

However, most modern scholars believe in a more recent theory: that by assuming the exclusively male symbols of pharaonic power, Hatshepsut was asserting her claim to be King or Queen regnant and not "King's Great Wife" or Queen consort. Even after assuming the male persona, Hatshepsut still described herself as a beautiful woman, often the most beautiful woman, and although she assumed almost all of her father's titles, she declined to take the title "The Strong Bull".

While the queen-pharaoh had herself depicted in art wearing the masculine regalia of the king, such as the false beard, it is most unlikely that she actually wore such ceremonial decorations. Statues such as the ones at the Metropolitan Museum of Art depicting her seated wearing a tight-fitting dress and the nemes crown are a more accurate representation of how she would have presented herself.

One of the most famous pieces of her propaganda is a myth about her birth. In this myth, Amun goes to Ahmose in the form of Thutmose I and awakens her with pleasant odors. At this point Amun places the ankh, a symbol of life, to Ahmose's nose, and Hatshepsut is conceived. Khnum, the god who forms the bodies of human children, is then instructed to create a body and ka, or corporal presence/life force, for Hatshepsut. Khnum and Heket, goddess of life and fertility, leads Ahmose along to a lion bed where she gives birth to Hatshepsut.

To further strengthen her position; the Oracle of Amun proclaimed that it was the will of Amun that Hatshepsut be Pharaoh. She publicized Amun's support by having endorsements by Amun carved on her monuments:

- Welcome my sweet daughter, my favorite, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkare, Hatshepsut. Thou art the Pharaoh, taking possession of the Two Lands.

She also claimed that she was her father's intended heir and that he made her crown prince of Egypt. Most scholars see this as revisionism on Hatshepsut's part, but one of her best-known biographers, Evelyn Wells, takes her at her word. Propaganda supporting her claim was commissioned on the walls of her mortuary temple:

- Then his majesty said to them: "This daughter of mine, Khnumetamun Hatshepsut, may she live! I have appointed as my successor upon my throne... she shall direct the people in every sphere of the palace; it is she indeed who shall lead you. Obey her words, unite yourselves at her command." The royal nobles, the dignitaries, and the leaders of the people heard this proclamation of the promotion of his daughter, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkare, may she live eternally.

She built magnificent temples as well as restoring many of the old ones, most notably the great mortuary temple at Deir al-Bahari.

Hidden for more than three millennia, it was

found in 1999 on the banks of the Nile River.

The mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut is one of the most dramatically situated in the world. The queen's architect, Senmut,designed it and set it at the head of a valley overshadowed by the Peak of the Thebes, the "Lover of Silence," where lived the goddess who presided over the necropolis. A tree lined avenue of sphinxes led up to the temple, and ramps led from terrace to terrace.

The porticoes on the lowest terrace are out of proportion and coloring with the rest of the building. They were restored in 1906 to protect the celebrated reliefs depicting the transport of obelisks by barge to Karnak and the miraculous birth of Queen Hatshepsut. Reliefs on the south side of the middle terrace show the queen's expedition by way of the Red Sea to Punt, the land of incense. Along the front of the upper terrace, a line of large, gently smiling Osirid statues of the queen looked out over the valley. In the shade of the colonnade behind, brightly painted reliefs decorated the walls.

Throughout the temple, statues and sphinxes of the queen proliferate.

Hatshepsut had begun construction of a tomb when she was the Great Royal Wife of Thutmose II, but the scale of this was not suitable when she became "king", so a second tomb was built. This was KV20, which was possibly the first tomb to be constructed in the Valley of the Kings. The original intention seems to have been to hew a long tunnel that would lead underneath her mortuary temple, but the quality of the limestone bedrock was poor and her architect must have realized that this goal would not be possible. As a result a large burial chamber was created instead. At some point it was decided to inter her father, Thutmose I from his original tomb in KV38 into a new chamber below her own. Her original red-quartzite sarcophagus was altered to accommodate her father instead, and a new one was made for her. It is likely that when she died (no later than the twenty-second year of her reign) she was interred in this tomb along with her father.

The tomb was opened in antiquity, the first time during the reign of Hatshepsut's successor, Thutmose III, who re-interred his grandfather Thutmose I to his original tomb, and then possibly moved Hatshepsut's mummy into the tomb of her wet nurse, In-Sitre, in KV60). Though her tomb had been largely cleared (save for both sarcophagi still present when the tomb was fully cleared by Howard Carter in 1903) some grave furnishings have been identified as belonging to the female pharaoh, including a "throne" (bedstead is a better description), a senet game board with carved lion-headed red-jasper game pieces bearing her kingly title, a signet ring, and a partial ushabti figurine bearing her name. In the Royal Mummy Cache at DB320 an ivory canopic coffer was found that was inscribed with the name of Hatshepsut and containing a mummified liver. However, there was a lady of the Twenty-first dynasty of the same name, and this could belong to her instead.

Changing Image

Towards the end of Thutmose III's reign an attempt was made to delete Hatshepsut from the historical and pharaonic record. This elimination was carried out in the most literal way possible. Her cartouches and images were chiselled off the stone walls - leaving very obvious Hatshepsut-shaped gaps in the artwork - and she was excluded from the official history that now ran without any form of co-regency from Thutmose II to Thutmose III. At the Deir el-Bahri temple Hatshepsut's numerous statues were torn down and in many cases smashed or disfigured before being buried in a pit. At Karnak there was even an attempt to wall up her obelisks. While it is clear that much of this rewriting of history occurred during the latter part of Thutmose's reign, it is not clear why it happened.

For many years Egyptologists assumed that it was a damnatio memoriae, the deliberate erasure of a person's name, image and memory, which would cause them to die a second, terrible and permanent death in the afterlife. This appeared to make sense. Thutmose must have been an unwilling co-regent for years. But this assessment of the situation is probably too simplistic. It is highly unlikely that the determined and focused Thutmose, not only Egypt's most successful general, but an acclaimed athlete, author, historian, botanist and architect, would have brooded for two decades before attempting to avenge himself on his stepmother.

Furthermore the erasure was both sporadic and haphazard, with only the more visible and accessible images of Hatshepsut being removed. Had it been more complete we would not now have so many images of Hatshepsut. It seems that Thutmose must have died before his act of vengeance was finished, or that he never intended a total obliteration of her memory at all. In fact, we have no evidence to support the assumption that Thutmose hated or resented Hatshepsut during her lifetime. Had he done so he could surely, as head of the army (a position given to him by Hatshepsut, who was clearly not worried about her co-regent's loyalty), have led a successful coup.

It may well be that Thutmose, lacking any sinister motivation, was, towards the end of his life, simply engaged in 'tidying up' his personal history, restoring Hatshepsut to her rightful place as queen regent rather than king. By eliminating the more obvious traces of his female co-regent, Thutmose could claim all the achievements of their joint reign for himself.

The erasure of Hatshepsut's name, whatever the reason, allowed for her to disappear from Egypt's archaeological and written record. Thus, when 19th-century Egyptologists started to interpret the texts on the Deir el-Bahri temple walls (which were illustrated with two obviously male kings) their translations made no sense. Jean-Francois Champollion, the French decoder of hieroglyphs, was not alone in feeling confused by the obvious conflict between words and pictures.

Of interest on this topic is the recent discovery of nine golden cartouches bearing the names of both Hatshepsut and Thutmose III near the obelisk at Hatshepsut's temple in Luxor. Further study may shed additional light on the question of their relationship and the eventual attempt to erase Hatshepsut from the historical record.

Popular Culture

As the Feminist movement matured, prominent women from antiquity were sought out and their achievements became increasingly publicized. Hatshepsut went from being one of the most obscure leaders of Egypt at the beginning of the 20th century to one of its most famous by the century's end. Biographies such as Hatshepsut by Evelyn Wells romanticized her as a beautiful and pacifistic woman - "the first great woman in History". This was quite a contrast to the 19th-century view of Hatshepsut as a wicked step mother usurping the throne from Thutmose III.

The novel Mara, Daughter of the Nile by Eloise Jarvis McGraw, maintains the wicked step-mother view by casting Hatshepsut as the story's villainess. The plot revolves around the efforts of the slave girl Mara and various nobles to overthrow Hatshepsut and install the "rightful" heir, Thutmose III, as Pharaoh. They blame Hatshepsut's numerous building projects for the bankruptcy of the Egyptian state and she is depicted as keeping Thutmose III as a prisoner within the palace walls. In 1960 a small main belt asteroid discovered by Cornelis Johannes van Houten, Ingrid van Houten-Groeneveld and Tom Gehrels was named 2436 Hatshepsut in her honor. There is a popular theory that states that Hatshepsut was the princess who found Moses floating in the Nile, which has been largely debated by Egyptologists and Biblical scholars.

At least three authors have written historical fiction novels featuring Hatshepsut as the heroine: Hatshepsut: Daughter of Amun by Moyra Caldecott, Child of the Morning by Pauline Gedge and Pharaoh by Eloise Jarvis McGraw, and the Lieutenant Bak series of mystery novels is set during her reign. Hatshepsut also figures into the plot of Illinois Jane and the Pyramid of Peril, a comic play by T. James Belich (Colorado Tolston), in which Hatshepsut is supposed to have discovered the Elixir of Life. In this story, Hatshepsut's disappearance is attributed to her resulting immortality, although she is never directly seen as part of the play.

In the live action children's show, The Secret of Isis (1975), the main character, Andrea Thomas, discovers an ancient Egyptian magic amulet and learns she is a descendent of Hatshepsut and heir to the powers of Isis. Hatshepsut is referenced in the opening narration.

Hatshepsut disappeared in 1458 B.C. when Thutmose III, wishing to reclaim the throne, led a revolt. Thutmose had her shrines, statues and reliefs mutilated.

Hatshepsut died, either as she was approaching or just entering middle age, in her twenty second regnal year; no record of her cause of death has survived. However, if the recent identification of her mummy in KV60 is correct, CT scans of the mummy indicate that she died of metastatic bone cancer in her 50s. For a long time, her mummy was believed to be missing from the Deir el-Bahri Cache. An unidentified female mummy, found with Hatshepsut's wet nurse Sitre In and with her arms posed in the traditional burial style of pharaoh, has led to the theory that an unidentified mummy in KV60 might be Hatshepsut.

In March 2006, Zahi Hawass claimed to have located the mummy of Hatshepsut, which was mislaid on the third floor of the Cairo Museum. On June 26, 2007 it was announced that Egyptologists believe they have identified Hatshepsut's mummy in the Valley of the Kings; this discovery is considered to be the "most important find in the Valley of the Kings since the discovery of King Tutankhamun". Decisive evidence was a molar in a wooden box inscribed with Hatshepsut's name, found in 1881 in a cache of royal mummies hidden away for safekeeping in a near-by temple. The tooth was found to have been removed from the mummy's mouth beyond doubt.

12/10/00 - I flew over the Temple of Hatshepsut in a hot air balloon .

Egyptologists say they have identified the 3,000-year-old mummy of Hatshepsut

BBC - June 27, 2007

Egypt's Female Pharaoh Revealed by Chipped Tooth, Experts Say

National Geographic - June 27, 2007

Hatshepsut Mummy Photo Gallery National Geographic - June 27, 2007

0 comments:

Post a Comment